Humans have always had a thing about the afterlife. The idea that we either land in eternal paradise or face never-ending punishment has shaped religions, cultures, and even pop culture.

Think of every movie where someone meets a glowing white figure at the pearly gates or wakes up in a fiery pit of doom.

But here’s the twist. Heaven and Hell weren’t always part of the plan. Early civilizations thought the afterlife was just a shadowy, quiet place.

No golden streets, no lakes of fire, just a dull, never-ending existence. Then, as beliefs evolved, the concept of moral justice kicked in.

Do good things, you get rewarded. Mess up, and it’s game over.

The road from ancient underworlds to the Heaven vs. Hell showdown we know today is a wild one.

The Sumerians had a gloomy underworld, the Egyptians came up with a VIP-only paradise, and the Greeks? They had a little bit of everything.

Eventually, Christianity and Islam took the idea to the next level with clear-cut rules on who gets in and who doesn’t.

So how did we get here? What changed over the centuries to turn Heaven and Hell into the ultimate destinations? That’s what we’re about to find out.

Dawn of Afterlife Beliefs (Pre-1500 BCE)

Long before Heaven and Hell became the ultimate destinations, ancient civilizations had a much simpler view of the afterlife. There were no divine rewards, no fiery pits, just a continuation of existence in some form.

Death was inevitable, and what happened next was just another phase of being, not a cosmic judgment.

For most early cultures, the afterlife was neutral, a shadowy reflection of earthly life. Some societies believed in underground realms where souls wandered forever.

Others thought the dead stuck around as spirits, influencing the living. A few even believed that if you weren’t a king or a hero, you simply ceased to exist.

Sumerians: Welcome to the Land of No Escape

In ancient Mesopotamia, the Sumerians described the afterlife as Kur, sometimes called Irkalla. This was a universal underworld where all people ended up regardless of social status or moral choices.

Unlike later concepts of paradise and punishment, Kur was not about justice but inevitability. The dead were thought to survive as weak shadows of their former selves.

Life in Kur was bleak. Spirits relied on offerings from the living to sustain them, and without those offerings they languished in hunger and thirst.

It was not a place of fire or torment, but it lacked joy, hope, or reward. In this early vision, death meant a permanent separation from vitality and light, endured by everyone without exception.

Egyptians (Old Kingdom): Pharaohs Get Eternal Life, You Don’t

In the Old Kingdom, it is true that pharaohs dominated afterlife narratives. Pyramid Texts inscribed within royal tombs describe their journeys with Ra or Osiris, ensuring divine status after death.

Commoners, by contrast, seemed excluded from eternity, their lives ending in silence.

Yet archaeology complicates this picture. Elites and some officials were buried with modest grave goods and ritual protections.

These suggest a belief that select non-royals could share a limited afterlife, even if not on the same scale as kings. Access to eternity may have been tied to wealth and ritual investment, not purely to kingship.

Over time, this exclusivity softened. By the Middle Kingdom, Coffin Texts appeared in non-royal burials, and later the Book of the Dead spread the promise of judgment and renewal to wider society.

The Old Kingdom therefore represents less a total denial of afterlife for commoners, and more the early phase of a system that gradually democratized eternity.

Early Chinese Beliefs: Ancestors Still Matter

In early Chinese traditions, the afterlife was closely tied to ancestor veneration. The dead did not leave entirely but became shen, spirits who remained linked to their families.

These spirits could bring harmony, protection, or misfortune, depending on how they were honored by descendants. Offerings of food, incense, and spirit money at household altars ensured the well-being of the departed in the unseen world.

Neglecting these duties carried risks. Spirits without proper care might become restless hungry ghosts (èguǐ), wandering between realms and causing harm.

Rooted in early religious practices and later reinforced by Confucian and Daoist traditions, this system emphasized continuity and respect rather than judgment. The focus was not on paradise or punishment, but on the ongoing relationship between the living and the dead.

Indus Valley Civilization: The Mystery of the Dead

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE) remains enigmatic when it comes to afterlife beliefs. No surviving texts describe their views on death, but archaeological evidence offers important clues.

Careful burials, often including tools, ornaments, or pottery, suggest a belief that the dead required preparation for another stage of existence beyond life.

What that stage looked like remains unclear. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, there is no evidence of structured heavens, hells, or divine judgment.

The grave goods hint at a belief in continuity, but the details have been lost. For now, the Indus Valley leaves us with questions rather than answers, highlighting how much about early afterlife traditions remains hidden.

The Big Picture

In the earliest civilizations, the afterlife was not a place of moral accountability. Instead, it reflected broader social and cultural structures.

Mesopotamia imagined a single, neutral underworld; Egypt gave rulers exclusive access to eternity; China emphasized family bonds and ritual continuity; and the Indus Valley hinted at ongoing existence without clear doctrine.

Across these traditions, what mattered most was survival, memory, and the maintenance of connections between the living and the dead. Ideas of judgment, reward, and punishment had not yet taken shape, but the foundations were being laid for the dramatic shifts to come.

The Shift from Neutral Afterlife to Moral Judgment (1500 BCE – 500 BCE)

In the early days, the afterlife was like a one-size-fits-all waiting room, everyone ended up in the same place, no questions asked. But between 1500 BCE and 500 BCE, things got interesting.

Cultures started thinking that maybe, just maybe, what you did while alive could affect your afterlife accommodations. Let’s dive into how this idea of moral judgment after death took root.

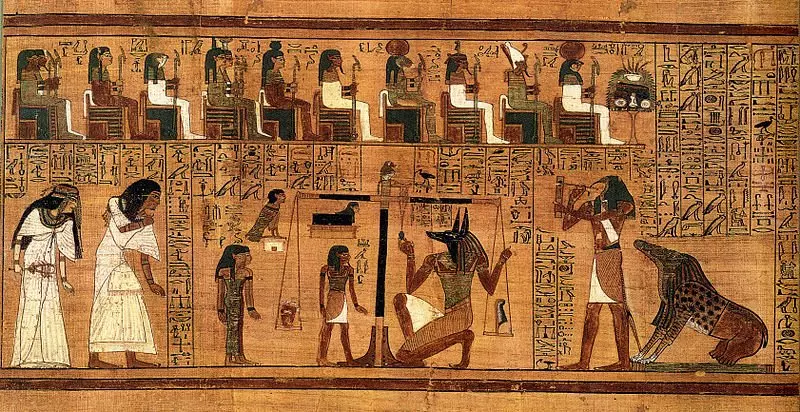

Egyptians Level Up: The Weighing of the Heart

By the Middle and New Kingdoms, Egypt’s afterlife took on a clear moral edge. At judgment, a person’s heart – the seat of memory and conscience – was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, symbol of truth and balance.

This scene, made famous in Book of the Dead spell 125, introduced ethical review into what had once been mostly royal privilege.

If the scales balanced, the soul entered the Field of Reeds, an idealized Egypt of family, fields, and festivals. If the heart proved heavy with wrongdoing, the hybrid creature Ammit – part crocodile, lion, and hippopotamus – devoured it, ending the person’s chance at continued existence.

The outcome was not torment but nonexistence, a powerful deterrent against injustice.

Texts, amulets, and funerary rites now aimed to align a person with Ma’at. The famous “Negative Confession” (“I have not stolen… I have not murdered…”) tied everyday ethics to cosmic order.

In this era, morality, ritual knowledge, and divine justice fused, making right conduct the gateway to eternal life.

Hindu Vedic Traditions: Karma’s Early Days

In Vedic India, ideas of karma and dharma began shaping afterlife expectations. Karma represented the law of cause and effect, where actions in one life influenced outcomes in future lives.

Dharma, or righteous duty, determined whether a soul (ātman) ascended to Svarga, the heavenly realm ruled by gods like Indra, or descended into Naraka, a temporary place of suffering where souls repaid the weight of their misdeeds.

These destinations were not permanent. Unlike eternal heaven or hell, both Svarga and Naraka were stops along the cycle of samsāra – rebirth and reincarnation.

The ultimate goal was to reach moksha, liberation from the cycle altogether, where the soul united with Brahman, the universal spirit. In this system, morality was crucial, but the focus was on spiritual progress rather than eternal reward or punishment.

Zoroastrianism: The Original Heaven and Hell

Emerging in ancient Persia, Zoroastrianism presented one of the earliest fully structured afterlife systems. Souls faced judgment at the Chinvat Bridge, where deeds were weighed by divine forces.

The righteous crossed safely into the House of Song (Garōdmān), a realm of light, harmony, and closeness to Ahura Mazda, the supreme god. The wicked, however, found the bridge narrowing to a razor’s edge, plunging them into the House of Lies (Druj Demana), a dark wasteland of chaos and torment.

This sharp division reflected the religion’s dualism: good versus evil, order versus chaos. It was also profoundly influential.

Elements of Zoroastrian eschatology later shaped Jewish, Christian, and Islamic ideas of judgment, paradise, and damnation. By linking morality directly to eternal destiny, Zoroastrianism established the blueprint for the Heaven-and-Hell dichotomy that dominates much of later thought.

Mesoamerican Myths: Cosmic Realms and Underworlds

Mesoamerica wasn’t a single system. Among the Maya, the underworld Xibalba (known from the Popol Vuh) tested souls with houses of trials – cold, darkness, blades, and deception.

Ritual knowledge, divine favor, and heroic precedent shaped the journey. Some rulers and culture heroes were envisioned ascending to celestial realms, joining cycles of the sun or maize renewal.

For the Aztec (Mexica), fate after death depended largely on manner of death, not personal morality. Warriors who died in battle (and women who died in childbirth) joined the sun’s retinue; those who drowned or died by water went to Tlālōcān, a lush, watery paradise of the rain god Tlāloc.

Most others traveled through Mictlan, a nine-level underworld reached after years of arduous passage. Tamoanchan – a mythic place of creation – belongs to Aztec cosmology rather than Maya belief.

Taken together, these traditions show sophisticated, non-binary afterlives. Outcomes turned on ritual roles, cosmic cycles, and death’s circumstances more than courtroom-style judgment.

The result is a rich map of destinations and ordeals, where sacred knowledge and cosmic alignment – not a simple moral ledger – shape the soul’s next stage.

The Big Picture: Morality Matters Now

Between 1500 BCE and 500 BCE, the afterlife was redefined. Instead of a universal shadowland, it became a moral landscape where choices in life carried weight after death.

Egyptians measured hearts, Vedic India balanced karma, Persians crossed a cosmic bridge, and Mesoamericans braved underworld trials.

This shift didn’t only reshape religion. It influenced daily behavior, emphasizing ethical action and ritual preparation as ways of securing a favorable outcome.

For the first time in history, the afterlife was no longer simply about survival – it became a realm of judgment, consequence, and moral order.

The Rise of Structured Afterlife in Early Monotheistic Religions (500 BCE – 500 CE)

Between 500 BCE and 500 CE, the afterlife went through a major transformation. Early monotheistic religions started laying down the law: behave, and you’re in for paradise; mess up, and, well, eternal consequences await.

Let’s see how these ideas took shape across different faiths.

Judaism: From Sheol to the World to Come

In the Hebrew Bible, the dead were gathered in Sheol, a silent underworld where both righteous and wicked shared the same fate. It was not imagined as a fiery pit or blissful paradise, but as a neutral resting place that underscored death as separation from God and community.

During the Second Temple period, Jewish thought diversified. Some writings emphasized resurrection, envisioning a restored creation where the faithful would rise again.

Others leaned toward annihilationism, in which the wicked would simply cease to exist. Still others drew on messianic hope, tying justice in the afterlife to the arrival of God’s kingdom on earth.

Later Rabbinic Judaism introduced new layers. The idea of Olam Ha-Ba (“the World to Come”) promised reward for the righteous, while Gehinnom was described as a temporary place of purification rather than eternal torment.

Rather than one fixed doctrine, Jewish eschatology remained a spectrum of views that reflected ongoing dialogue about justice, resurrection, and divine mercy.

Early Christianity: Heaven and Hell Defined

Christianity sharpened afterlife ideas inherited from Jewish apocalyptic thought. Heaven was imagined as eternal communion with God, a realm of joy and divine presence.

Gehenna, drawn from the Valley of Hinnom outside Jerusalem, became the primary image for Hell, symbolizing fire, decay, and exclusion from God’s light rather than a mere rubbish heap.

Jesus’ parables often set dramatic contrasts: faithful servants welcomed into the kingdom, the careless or corrupt cast out. Early Christian writings expanded these themes, teaching that choices in life carried eternal weight.

Heaven and Hell became central to daily morality, pressing believers to see their destiny as shaped by every decision.

Yet diversity remained. Some Christians taught annihilationism, where the wicked simply perished. Others, like Origen, speculated about universal reconciliation, the eventual restoration of all souls.

Over time, however, the dual model of eternal reward and eternal loss came to dominate, embedding itself in Western theology, art, and imagination for centuries.

Buddhism: Naraka and the Cycle of Rebirth

In Buddhist cosmology, the afterlife is not final judgment but part of samsara, the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Beings with negative karma could fall into Naraka, a realm of intense suffering filled with cold, fire, and torment.

Unlike the eternal Hell of Christianity, Naraka was temporary – a place of karmic purification rather than permanent damnation.

Positive karma led to higher rebirths, including realms of gods and celestial beings, but even these were impermanent. The ultimate aim was nirvana, liberation from samsara altogether.

This framework highlighted that actions have consequences, but it also stressed impermanence: even punishment and reward are transient stages on the soul’s path to enlightenment.

The Big Picture: Moral Accountability Takes Center Stage

Between 500 BCE and 500 CE, the afterlife became more structured and more moralized. Judaism shifted from Sheol to resurrection and the promise of a perfected world.

Christianity drew clear lines between Heaven and Hell, setting the stage for later Western theology. Buddhism offered a system where deeds shaped rebirths, emphasizing impermanence and the goal of release.

Across these traditions, accountability became central. Death was no longer just transition or continuity – it was the arena where justice, divine order, and cosmic balance determined the soul’s ultimate path.

Medieval Theological Refinements (500 CE – 1400 CE)

Between 500 CE and 1400 CE, the concepts of Heaven and Hell got a serious makeover. Religions didn’t just talk about the afterlife; they painted vivid pictures of what awaited us, using art, literature, and teachings to make it all feel real.

Let’s explore how different cultures during the medieval period reimagined the great beyond.

Catholic Christianity: Dante’s Guided Tour of the Afterlife

In medieval Europe, Christianity gave the afterlife vivid detail through theology, art, and literature. The most influential work was Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (14th century), which mapped Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in astonishing detail.

Dante’s Inferno described nine circles of Hell where sinners endured punishments mirroring their sins, from gluttons wallowing in filth to traitors frozen in ice.

Beyond Hell, Purgatorio depicted a transitional realm where souls purified themselves before entering Paradiso, a vision of divine light and harmony. Though a literary creation, Dante’s imagery became deeply embedded in Christian imagination, reinforcing moral accountability and shaping how Europe envisioned the afterlife for centuries.

Islamic Theology: Mapping the Afterlife

In Islam, the Qur’an and Hadith presented a structured moral vision of the afterlife. The righteous were promised Jannah, a paradise of gardens, rivers, and eternal peace, where believers found reward for their faith and good deeds.

Entry depended on obedience to God, moral conduct, and divine mercy.

For the wicked, the destination was Jahannam, a layered hell with punishments scaled to the severity of sins. Some souls endured temporary purification before being granted mercy, while others remained in eternal suffering.

These depictions gave the Islamic afterlife both structure and moral depth, emphasizing accountability and underscoring the belief that choices in life shaped eternal outcomes.

Norse Mythology: Warrior’s Paradise vs. the Underworld

Norse beliefs about the afterlife were not limited to Valhalla’s feasting halls or Helheim’s cold stillness. While fallen warriors might be chosen by Valkyries to dwell with Odin in Valhalla, many others found their way to different destinations depending on fate, courage, and circumstance.

Some slain in battle went instead to Fólkvangr, the field of the goddess Freyja, where they shared her company rather than Odin’s. Sailors claimed by the sea were thought to rest with Rán, a goddess who gathered the drowned into her watery domain.

Meanwhile, spirits of the dead were often believed to linger near their burial mounds, influencing the living as protectors or restless ghosts.

These varied afterlife routes reflect the Norse sense of fate (Old Norse: urðr), or destiny. Death in battle secured honor and community among gods, while a quiet or dishonorable death meant a colder, lonelier existence.

The afterlife mirrored life’s values: bravery, loyalty, and acceptance of fate determined one’s eternal place.

Tibetan Buddhism: Navigating the Bardo

In Tibetan Buddhism, death was seen as a transition rather than an end. Consciousness (mindstream) traverses the Bardo, an intermediate state between death and rebirth.

Described in the Bardo Thodol (Tibetan Book of the Dead), this stage included visions of peaceful Buddhas or terrifying deities, all manifestations of the mind.

Recognizing these experiences as illusions allowed the soul to escape rebirth and reach nirvana. Failure to recognize them led to rebirth in higher or lower realms, depending on accumulated karma.

Tibetan teachings stressed preparation for death through meditation and awareness, making the Bardo not just a doctrine but a guide for living consciously toward liberation.

The Big Picture: Afterlife Imagery Shapes Belief and Behavior

The medieval period brought a surge of detailed imagery about the afterlife. Christianity dramatized Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory; Islam mapped Jannah and Jahannam with moral clarity; Norse culture contrasted Valhalla’s glory with Helheim’s stillness; Tibetan Buddhism offered a psychological and spiritual guide through death.

These portrayals did more than fill imagination – they guided behavior. By making the afterlife vivid and personal, religions encouraged followers to act in ways that matched their values, reinforcing social order and deepening the role of moral accountability in daily life.

The Renaissance & Enlightenment Shift (1400 CE – 1800 CE)

Between 1400 and 1800 CE, the afterlife’s VIP sections, Heaven and Hell, faced some serious scrutiny. As science and reason gained traction, folks started questioning age-old beliefs about what happens after we kick the bucket.

Let’s see how this period shook up our ideas of the great beyond.

European Christianity: Reformation Remix

In the late Middle Ages, Catholic teaching emphasized Purgatory, a place where souls were cleansed before entering Heaven. Over time, practices like the sale of indulgences – payments meant to reduce time in Purgatory – caused growing controversy.

By the early 16th century, this tension boiled over.

In 1517, Martin Luther challenged indulgences in his Ninety-Five Theses, sparking the Protestant Reformation. Reformers rejected Purgatory altogether, emphasizing salvation through faith alone (sola fide).

This theological shift reshaped European Christianity, creating lasting divides over judgment, forgiveness, and the mechanics of the afterlife.

Deism and Secular Thought: The Age of Reason

The Enlightenment encouraged people to rethink religion through reason and science. Thinkers like Voltaire and Thomas Paine promoted Deism, which acknowledged a Creator but denied divine intervention in human affairs.

God was imagined as a “cosmic clockmaker” who set the world in motion but no longer interfered.

This outlook weakened the centrality of Heaven and Hell. Instead, emphasis shifted to morality, rationality, and human progress in the present world.

For many Enlightenment thinkers, ethics did not need divine reward or punishment – virtue could stand on reason alone. This laid the groundwork for modern secularism.

China & Confucianism: Keep It Real

While Europe debated theology, Confucianism in China continued to focus on earthly duties. The afterlife mattered less than living properly: maintaining filial piety (xiao), upholding social order (li), and cultivating personal virtue.

Ancestor worship remained important, but it was framed as respect for family lineage rather than securing posthumous rewards.

This pragmatic view emphasized the here and now. By teaching that harmony in family and society was the path to meaning, Confucian thought encouraged people to focus less on divine judgment and more on practical ethics.

This perspective shaped Chinese life for centuries, balancing ritual tradition with social responsibility.

Folk Spirituality: Ghosts and Ghouls Galore

Outside formal religion and philosophy, folk beliefs kept the spirit world close to daily life. Many cultures feared restless spirits, honored ancestors, and told stories of supernatural beings.

In China, hungry ghosts (èguǐ) symbolized neglected ancestors, while in Europe, spirits like banshees warned of death. In the Americas, legends such as La Llorona reinforced moral lessons through haunting tales.

Even as rationalism spread, folk spirituality ensured that the dead remained part of the living world. Ghost stories, rituals, and local practices blended fear, respect, and tradition, preserving connections to the unseen while entertaining and instructing communities.

The Big Picture: Shifting Focus

Between 1400 and 1800, the afterlife narrative fractured. Europe wrestled with theological reform, philosophy moved toward reason and secular ethics, China emphasized social duty over divine judgment, and folk traditions kept spiritual imagination alive.

The common thread was transition. Traditional Heaven-and-Hell models were questioned, redefined, or reinterpreted, paving the way for a more pluralistic view of what comes after death.

By the end of this era, the afterlife was no longer a single narrative but an open field for debate, faith, and imagination.

The Modern Era – Science, Secularism, and Spiritualism (1800 CE – 1950 CE)

From the 19th to the mid-20th century, our ideas about the afterlife took some unexpected turns. Science and secularism started calling the shots, but that didn’t stop people from trying to chat with the dead.

Let’s dive into how Heaven and Hell got reimagined during this time.

Science and Secularism: Questioning the Afterlife

The 19th century brought dramatic change. With the Industrial Revolution and advances in medicine, astronomy, and biology, science challenged long-held religious beliefs.

Darwin’s theory of evolution questioned humanity’s divine origins, while neurology suggested consciousness came from the brain rather than an immortal soul. These insights shook confidence in eternal Heaven or Hell.

Philosophers and intellectuals began to focus on meaning in the present world. The rise of secular existentialism placed morality and purpose in human choice, not divine decree.

The afterlife didn’t disappear from thought, but it was no longer assumed to be central or guaranteed.

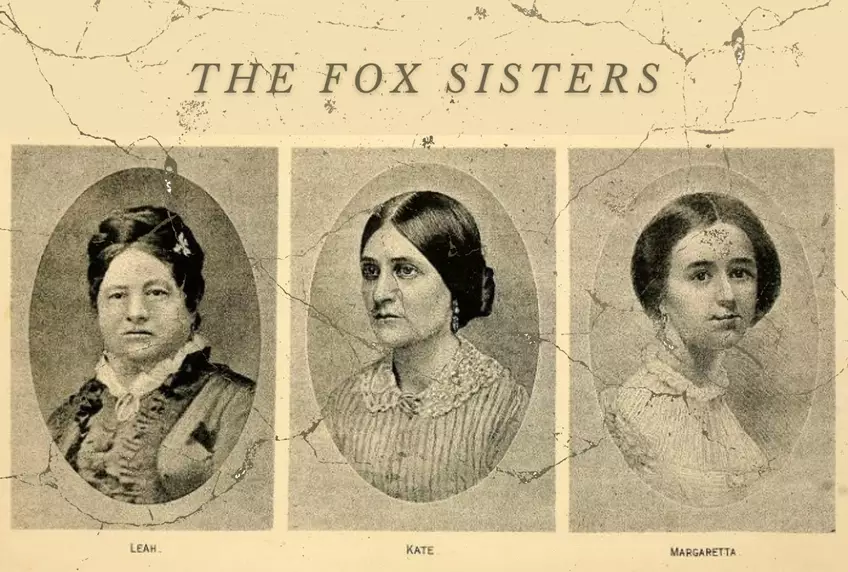

The Rise of Spiritualism: Ghosts in the Parlor

The Spiritualist movement of the 19th century was more than parlor entertainment. It arose during an age of grief, when wars and epidemics left families searching for comfort.

In 1848, the Fox sisters in New York claimed to communicate with spirits through mysterious raps, sparking a movement that spread rapidly across America and Europe.

Its popularity grew during the American Civil War and later World War I, when mass death created an urgent desire for contact with the departed. Séances, spirit photographs, and table-turning offered hope that loved ones were not lost forever.

Spiritualism combined ritual with new technologies, giving the supernatural a modern edge.

Though skeptics exposed frauds, Spiritualism endured because it filled a need that science could not – bridging grief with belief. It blurred the line between faith and experiment, comfort and spectacle.

More than a fad, it became a cultural response to loss, influencing how entire generations thought about death and the possibility of survival beyond it.

The Big Picture: A Fork in the Afterlife Road

Between 1800 and 1950, humanity split in two directions. Science and secularism explained death in material terms, stripping away certainty of Heaven and Hell.

At the same time, Spiritualism insisted the dead could still reach the living, keeping mystical traditions alive in new forms.

This duality set the stage for modern beliefs: a world where rationalism and skepticism coexist with fascination for the supernatural. The afterlife was no longer a single narrative – it became a contested space, shaped as much by science as by society’s longing for connection with the beyond.

Modern Views on the Afterlife & The Future of Heaven and Hell (1950 CE – Today)

From 1950 onwards, our ideas about the afterlife have been on a wild ride. With science, pop culture, and personal spirituality all throwing in their two cents, the classic notions of Heaven and Hell have gotten a serious makeover.

Let’s break down how our modern world is reshaping what happens after we kick the bucket.

Heaven and Hell in Pop Culture: From Fire and Brimstone to The Good Place

From the mid-20th century onward, film, television, and literature reshaped the afterlife into creative stories. Movies such as Beetlejuice and What Dreams May Come portrayed surreal visions of the beyond – sometimes bureaucratic, sometimes deeply personal.

These depictions departed from medieval fire-and-brimstone images, making the afterlife more accessible to modern audiences.

Television series like The Good Place approached the afterlife as a moral experiment, mixing humor and philosophy. Pop culture transformed Heaven and Hell into flexible settings for exploring ethics, identity, and human choice, showing that the afterlife could be playful as well as profound.

Near-Death Experiences (NDEs): Science Meets the Supernatural

Since the 1970s, reports of Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) have drawn wide attention. People describe bright lights, out-of-body journeys, or meetings with deceased relatives.

For many, these accounts suggest a glimpse of the afterlife, offering comfort that consciousness survives beyond the body.

Scientists, however, often explain NDEs as neurological responses to oxygen deprivation, brain chemistry, or psychological stress. Studies show recurring patterns across cultures but no definitive proof.

The debate keeps NDEs at the center of afterlife research, bridging science and spirituality and fueling public fascination with what might await after death.

Rise of Non-Religious Spirituality: DIY Afterlife Beliefs

With declining participation in organized religion, many people have crafted personalized spiritual frameworks. Instead of fixed doctrine, individuals combine elements from multiple traditions: reincarnation, energy transformation, or the continuation of consciousness beyond the physical body.

This flexibility reflects a desire for meaning without institutional boundaries.

Such “DIY spirituality” treats the afterlife as a field of exploration rather than dogma. It allows people to adapt beliefs to personal experiences and cultural influences.

In doing so, it keeps the question of Heaven and Hell alive but shifts focus toward individual interpretation and self-directed faith.

Simulation Theory & AI: Uploading Consciousness?

In the modern age, visions of the afterlife have expanded beyond religion into the language of technology. Simulation Theory suggests our reality could itself be a vast computer program, with death as little more than logging off or transferring into another simulation.

Meanwhile, advances in AI and neuroscience inspire speculation about uploading human consciousness into digital form.

These ideas are not traditional belief systems – they lack the rituals, moral codes, and communal practices that define religion. Instead, they function as philosophical thought experiments and futuristic possibilities.

They raise questions about identity, continuity, and whether immortality can be engineered rather than divinely granted.

What makes these theories compelling is how they echo humanity’s oldest desires: survival, memory, and transcendence. While still speculative, they push the boundaries of how we imagine life after death.

They do not replace Heaven or Hell but add a new dimension to the ever-evolving debate about what awaits beyond mortality.

The Big Picture: Afterlife 2.0

Today, the afterlife is no longer a single narrative but a wide spectrum of possibilities. Some continue to hold traditional views of Heaven and Hell, while others embrace reincarnation, digital consciousness, or energy-based survival.

Pop culture, NDE research, and technology all contribute to a dynamic and evolving discussion.

What unites these perspectives is curiosity. Humanity has never stopped asking what happens after death – it has only changed the language and frameworks of the answer.

The afterlife remains a mirror for our values, fears, and hopes about the future.

Sources and References

“Death and Afterlife: Themes & Beliefs“

StudySmarter

This article explores ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, including the journey to the underworld and judgment by Osiris.

“Afterlife Beliefs: Religions & Themes“

Vaia

This source delves into various religious perspectives on the afterlife, including those of ancient Egyptians and indigenous animistic religions.

“Beliefs and Rites: Funerals and Burial in Ancient Mesopotamia“

Brewminate

An examination of Mesopotamian afterlife beliefs, describing a dim underworld where souls led a shadowy existence.

“The Mythology of Afterlife Beliefs and Their Impact on Religious Conflict“

Brigid Burke, Religious Theory

This article discusses transformations in afterlife beliefs in the Near East around the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, highlighting the emergence of moral judgments in the afterlife.

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Religions: An Analysis of Cultural and Historical Transformations“

ResearchGate

This paper analyzes the evolution of ancient religious beliefs, including concepts of the afterlife across various cultures.

“Islamic Views on the Afterlife”

patheos

An exploration of Islamic teachings on life after death, including descriptions of paradise (Jannah) and hell (Jahannam).

“The Afterlife in Norse Mythology”

norse-mythology.org

This piece explores Norse beliefs about life after death, including Valhalla and Hell.