Introduction

The Div-e Sepid, literally “White Demon,” is one of the most memorable antagonists in the Shahnameh, the Persian epic composed by the poet Ferdowsi around the turn of the 11th century. Within the narrative cycle concerning the Iranian king Kay Kavus and the hero Rostam, the Div-e Sepid functions as the most formidable of the divs of Mazandaran.

In the epic, the demon is not a wandering monster but a structured adversary within a defined mythic geography. He leads the divs of Mazandaran and defeats Kay Kavus, blinding the king and his army.

This act sets in motion Rostam’s celebrated Haft Khan, or Seven Labors, culminating in the confrontation with the White Demon.

The episode is not incidental but central to Rostam’s heroic identity. The defeat of the Div-e Sepid restores the sight of the blinded Iranians through the demon’s blood, a detail explicitly preserved in traditional retellings.

The episode reinforces a recurring pattern in the epic: divine kingship falters through hubris, and the hero restores order through courage and strength.

The Div-e Sepid therefore stands as a literary embodiment of catastrophic opposition within the Iranian epic imagination: a concentrated obstacle whose defeat marks the reestablishment of political and cosmic stability.

History / Origin

The Div in Iranian Religious Background

The word div (Middle Persian: dēw, from Avestan daēva) originates in early Iranian religious vocabulary. In Zoroastrian tradition, the daēvas become associated with false or destructive powers opposed to the righteous order (asha).

This transformation reflects a broader Indo-Iranian religious shift in which certain divine beings were reclassified as malevolent.

By the Sasanian period and later literary traditions, div becomes the conventional Persian term for a demonic or hostile supernatural being. This background establishes the semantic framework in which the Div-e Sepid appears in epic literature.

The Shahnameh as Primary Narrative Source

The most detailed and authoritative account of the Div-e Sepid appears in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (completed c. 1010 CE). The episode is located in the cycle of Kay Kavus’s ill-fated expedition to Mazandaran, a region depicted in the epic as inhabited by powerful divs.

In the narrative, Kay Kavus ignores warnings and invades Mazandaran. The Div-e Sepid defeats him, blinds him and his warriors, and imprisons them.

Rostam is summoned to rescue the king. After overcoming several trials, Rostam confronts and kills the Div-e Sepid.

The demon’s blood is then used to restore the king’s sight.

This episode firmly anchors the Div-e Sepid in epic, not ritual, tradition. There is no evidence of cultic worship or independent myth cycle devoted to the White Demon outside literary contexts.

Mazandaran and Mythic Geography

Mazandaran in the Shahnameh is not merely a historical province but a mythologized landscape representing a liminal and hostile territory. The divs who inhabit it embody forces that stand outside Iranian royal order.

The Div-e Sepid’s status as leader of these beings reinforces his role as a territorial and political adversary rather than a random monster. His defeat restores sovereignty and reestablishes the moral and political hierarchy of the Iranian world.

Thus, historically and literarily, the Div-e Sepid emerges at the intersection of older Iranian demonology and medieval epic composition. His figure is best understood as a crystallization of inherited religious vocabulary within the narrative architecture of the Shahnameh.

Name Meaning

The name Div-e Sepid (Persian: دیو سپید) translates directly as “White Demon.” The word div (also written dīv) is the standard Persian term for a demonic or hostile supernatural being, inherited from the Avestan daēva.

In early Iranian religion, daēvas were rejected or condemned beings associated with falsehood and disorder in contrast to the righteous cosmic order.

By the time of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the term div had become fully integrated into epic vocabulary, referring to powerful, often monstrous adversaries who oppose Iranian kings and heroes. The title does not denote a species name but a rank or type within a broader category of hostile beings.

The second element, sepid, means “white.” The adjective distinguishes this particular demon from others in the Mazandaran cycle and functions as a defining epithet rather than a symbolic abstraction.

In the narrative, the whiteness is a physical marker of identity, making the Div-e Sepid visually and textually distinct among the divs.

The compound name therefore operates descriptively: it identifies a specific demon leader by color and status within the epic’s mythic geography. There is no evidence in primary sources that the color white in this case carries an inverted moral symbolism; the designation functions primarily as an identifying attribute.

Appearance

In the Shahnameh, the Div-e Sepid is described as immense and physically overwhelming. He is not a minor demon but the most powerful among the divs of Mazandaran.

The narrative emphasizes his strength, size, and ferocity rather than elaborate anatomical detail.

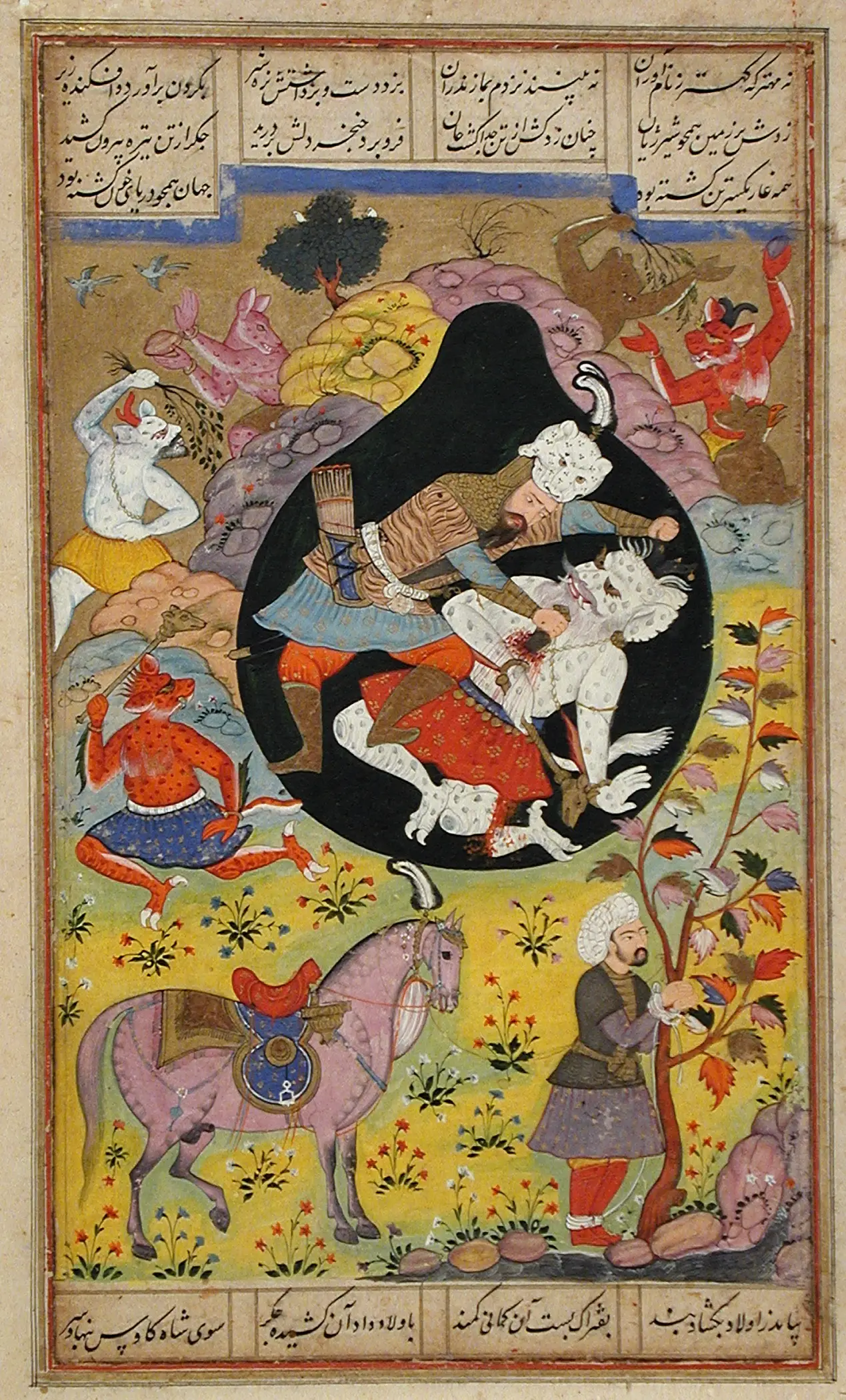

Illustrated manuscript traditions of the Shahnameh consistently depict the White Demon as a towering humanoid creature with pale or white skin, exaggerated musculature, and monstrous facial features. These visual traditions reinforce the epic’s emphasis on physical dominance and otherness.

The whiteness of the Div-e Sepid is central to his visual identity. In Persian miniature painting, this characteristic is often rendered through light-toned skin contrasted with darker human figures, visually marking him as both supernatural and alien to the Iranian courtly world.

The epic also attributes to him destructive power beyond brute strength. He commands other divs and is capable of defeating and blinding King Kay Kavus and his army.

His defeat requires not only physical combat but overwhelming heroic force from Rostam.

Across textual and visual sources, the Div-e Sepid is portrayed not as a subtle tempter or trickster but as a physically dominant, territorially rooted adversary. His body, color, and scale collectively signify his status as the supreme demonic obstacle in the Mazandaran episode.

Background Story

How the motif forms in Iranian demonology

Div-e Sepid grows out of an older Iranian vocabulary for hostile supernatural forces. Long before Ferdowsi, Iranian tradition already used div/dēw language for beings associated with deception, violence, and disorder.

By the medieval period, that demon category was fully available for epic storytelling: a div could be a concrete enemy in a heroic plot, while still carrying inherited “anti-order” associations.

Why Mazandaran becomes the right stage

In the Shahnameh, Mazandaran is not treated as ordinary geography. It functions as a mythic “outside” zone where royal authority fails and non-Iranian forces dominate.

Placing Div-e Sepid there gives the narrative a clear structure: Iran’s king enters the wrong space, loses control, and a hero must restore the boundary. This is why the White Demon feels less like a random monster and more like a territorial embodiment of threat.

Crystallization in Ferdowsi’s epic

The key point for accuracy: Div-e Sepid’s fame is not because he has dozens of independent folk cycles. His myth becomes durable because the Shahnameh locks him into one of the epic’s most repeated hero patterns: failed kingship, catastrophic punishment (blinding), then restoration through Rostam’s trial-journey.

Once the epic becomes a cultural backbone, the demon becomes a stable “name-anchor” for that entire arc, retold in recitation, illustration, and later adaptations.

What is and is not “Zoroastrian” here

It is tempting to present Div-e Sepid as a direct Zoroastrian figure aligned with Ahriman, but that overstates the evidence. Scholarship treats the episode as drawing on Iranian demon hostility and mythic memory, yet also notes that Div-e Sepid as a named character is not simply lifted from Zoroastrian canon.

In other words: the epic uses Iranian demon frameworks, then reshapes them into its own narrative logic.

Famous Folklore Stories

Kay Kavus’s Mazandaran disaster and the blinding of Iran’s court

A canonical story-cycle begins when Kay Kavus is drawn into the Mazandaran campaign and is defeated by the divs. Div-e Sepid is the crucial agent of catastrophe: through sorcery he blinds the king and his warriors, turning a political failure into a physical and symbolic collapse.

In performance tradition, this moment is the “hook” that makes Rostam’s rescue not optional but necessary.

Rostam’s Haft Khan and the killing of the White Demon

The most widely transmitted sequence is Rostam’s Haft Khan, whose final target is Div-e Sepid. The climax is typically staged in a dark cave, emphasizing that this adversary belongs to an “underworld” space even while remaining geographically located in Mazandaran.

Rostam’s victory is not just slaying: the demon’s blood is applied to the eyes of the blinded Iranians to restore sight, completing the narrative arc from disorder to repair.

India, Subimperial Mughal, 1608

The story as a visual tradition: why the scene is remembered the same way

Across major Shahnameh manuscript traditions, the White Demon episode becomes one of the most illustrated moments in Persian art. The repeated iconography, Rustam overpowering a pale, massive humanoid div in a cave-like setting, helps explain why this story persists so strongly across generations.

Even when retellings compress the Seven Labors, the White Demon fight is often preserved as the defining image of the entire cycle.

Cultural Impact

The Shahnameh as a cultural backbone

Div-e Sepid matters culturally because the Shahnameh matters culturally. As Ferdowsi’s epic became a core vessel for Persian language, memory, and heroic ideals, certain episodes gained exceptional durability.

The White Demon cycle is one of those episodes because it compresses a complete moral arc: royal overreach, catastrophic punishment, and restoration through heroic action.

In public imagination, Div-e Sepid functions less as a “character with evolving lore” and more as a stable emblem of overwhelming adversity. That stability is precisely why the figure survives across centuries of retelling even when details are abbreviated.

Performance tradition: epic recitation as transmission

The Div-e Sepid story persists through performance as much as through manuscripts. Iranian dramatic storytelling traditions preserve and refresh epic scenes by reciting them in ways adapted to audience and place, helping fixed story beats remain recognizable from generation to generation.

In that context, Div-e Sepid is not only a demon in a book. He is a dramatic “peak antagonist” used to showcase the storyteller’s control of tension, voice, gesture, and turning points, especially the reversal from blinding defeat to restored sight.

Visual tradition: why the White Demon scene is repeatedly remembered

Among the most reproduced images in Persian manuscript painting is the moment of Rostam overpowering the White Demon. This does two things culturally: it gives the episode a consistent visual shorthand, and it turns the story into an icon that can circulate independently of full-text reading.

Because the scene is so visually legible, later audiences often recognize the White Demon not by a long description, but by the recurring composition: a pale, massive div, a hero in dominance, and a cave-like setting that signals an “outside” zone of danger.

Similar Beasts

Akvan-e Div (Iranian epic demon)

Akvan-e Div is another major div slain by Rostam in Iranian epic tradition. Like Div-e Sepid, he is framed as a supernatural adversary whose defeat demonstrates not only strength but heroic decisiveness against nonhuman threat.

Unlike the White Demon’s territorial “final boss” role in Mazandaran, Akvan’s story emphasizes deceptive metamorphosis and magic. The shared function is clear: divs become narrative engines for trials that validate the hero.

Aždahā (Iranian dragon traditions)

Aždahā refers to dragon-type monsters in Iranian tradition, often enormous and associated with destructive power. Like Div-e Sepid, it represents a concentrated threat that heroes must overcome to restore safety and order.

The similarity is structural, not cosmetic. Both figures operate as “catastrophe containers”: single antagonists whose presence makes a landscape unsafe and whose removal marks a return to stability.

Rakshasa (South Asian demon figures)

Rakshasas in Hindu myth are demonic beings known for disrupting human order, often threatening communities and opposing righteous protagonists. Functionally, they resemble divs as hostile outsiders to the moral world of the story.

The parallel to Div-e Sepid is the role as an extreme antagonist that clarifies heroism through confrontation. The difference is that rakshasas appear across many cycles, while Div-e Sepid is anchored in a specific epic arc.

Jinn (Arabian and Islamic spirit beings)

Jinn are invisible spirits in Arabic mythology and Islamic belief, capable of assuming forms and exercising extraordinary power. They overlap with divs in that they provide a culturally familiar category for nonhuman agency and danger.

The key divergence is moral structure. Jinn are often described as capable of moral choice, while divs in the Shahnameh episode function as irreconcilable adversaries.

Similarity here is “supernatural other,” not identical ethics.

Humbaba (guardian-monster of the Cedar Forest)

Humbaba, the guardian of the Cedar Forest in Mesopotamian epic, resembles Div-e Sepid in narrative placement: a named monster stationed in a remote, dangerous zone that heroes must penetrate and survive.

Both figures operate as threshold guardians. The monster’s defeat is not random violence but a turning point that proves the protagonists can cross into the “forbidden” and return with restored status and story authority.

Shaitan as class of demonic forces in Islamic tradition

Shaitan is described as an unbelieving class of jinn in Islamic myth and also used as a term for the devil when performing demonic acts. The resemblance to Div-e Sepid is role-based: an adversarial force framed against moral order.

This is not a direct lineage claim. It is a comparison of how traditions personify opposition to righteousness into named categories that remain culturally legible across retellings.

Div-e Sepid compared to Akvan-e Div and Jinn

| Aspect | Div-e Sepid | Akvan-e Div | Jinn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | The Div-e Sepid originates from Persian mythology and the Shahnameh epic. | Akvan-e Div is also rooted in Persian folklore, appearing in various tales. | Jinn have origins in Arabian mythology, influencing many cultures over time. |

| Role in Mythology | In mythology, the Div-e Sepid serves as a primary antagonist to heroes. | Akvan-e Div plays a significant role as a formidable adversary in legends. | Jinn often act as both helpers and challengers in various narratives. |

| Symbolism | The White Demon symbolizes chaos, evil, and the struggle against tyranny. | Akvan-e Div represents deception and the challenges faced by heroes. | Jinn symbolize a range of forces, from benevolence to malevolence. |

| Depiction | Div-e Sepid is depicted as a powerful, white-skinned demon with fierce features. | Akvan-e Div is often illustrated as a dark, cunning figure in stories. | Jinn are depicted in diverse forms, from ethereal beings to monstrous shapes. |

| Powers | The Div-e Sepid possesses immense strength and the ability to blind foes. | Akvan-e Div is known for its cunning and magical abilities in confrontations. | Jinn have various powers, including shape-shifting and granting wishes. |

| Famous Stories | The story of Div-e Sepid culminates in Rostam's heroic labors against it. | Akvan-e Div features prominently in tales of heroism and trials faced by champions. | Jinn are central to many stories, often involving moral lessons and adventures. |

Scientific or Rational Explanations

Narrative logic: why the White Demon exists as a “peak obstacle”

From a literary lens, Div-e Sepid operates as a structurally necessary antagonist: the story needs a final adversary powerful enough to justify Rostam’s escalation through the Haft Khan, and coherent enough to concentrate the episode’s stakes into one decisive confrontation.

Symbolic mechanics: blindness and restoration as a social diagram

The Mazandaran cycle hinges on a repeated human pattern: royal hubris produces catastrophe, and a hero restores stability. The blinding of Kay Kavus and the court externalizes political failure into bodily harm, then reverses it through a vivid cure motif.

In that sense, the demon is less “random evil” and more a narrative tool that makes collapse and repair legible.

Cultural geography: Mazandaran as the “outside zone”

A common rational reading treats Mazandaran in the epic as a mythic frontier where ordinary sovereignty fails. The White Demon becomes the concentrated “face” of that frontier: an embodied threat that turns the king’s overreach into a tangible punishment, forcing the return of order through heroic intervention.

Myth as memory technology, not eyewitness report

From an anthropological perspective, the episode can be understood as a durable cultural memory machine: it packages warnings about reckless leadership, dramatizes the cost of misrule, and reinforces the hero as the agent who repairs communal damage. The demon’s physiology is less important than the functions the figure performs.

Modern Cultural References

Shahnameh: The Epic of the Persian Kings, illustrated book, Hamid Rahmanian (art/production) and Ahmad Sadri (adaptation/translation), 2013.

A modern illustrated edition that re-presents Rostam’s Haft Khan for contemporary readers, including the Div-e Sepid episode as a major visual set-piece within the Mazandaran rescue arc.

https://www.kingorama.com/epic-shahnameh

State of Play: شهر بازی, immersive interactive performance (Unreal Engine + live narration), year not specified.

A contemporary interactive installation/performance where participants progress through game-like levels and confront a boss explicitly named div-e sepid (white demon), reframing the figure in modern digital theater.

https://sharespace.eu/state-of-play-%D8%B4%D9%87%D8%B1-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B2%DB%8C/

NIMĀ YUŠIJ (entry noting a White Demon allusion), literary reference, year not specified.

A scholarly reference noting that modernist poet Nima Yushij alludes to the Shahnameh story of Rostam and the White Demon (Div-e Sepid), showing the figure’s afterlife in modern Iranian literature.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nima-yusij/

The White Demon Falls: Rostam’s Bloody Triumph, podcast episode (Poetry of Time), 2025.

A modern audio retelling that explicitly centers Rostam’s descent to the White Demon’s cave and the restorative use of the demon’s body/blood motif, presenting the episode for a contemporary audience.

https://podcasts.apple.com/eg/podcast/the-white-demon-falls-rostams-bloody-triumph-the/id1823297183?i=1000742224029

Shahnameh: Epic of the Persian Kings (museum program page), exhibition/program feature, Honolulu Museum of Art, year not specified.

Museum programming that frames Rahmanian’s contemporary illustrated Shahnameh project for modern audiences, sustaining recognition of key episodes (including Rostam’s demon combats) in public culture.

https://honolulumuseum.org/shahnameh-epic-of-the-persian-kings-cyw1

Conclusion

Div-e Sepid endures because he is anchored in one of the Shahnameh’s most transmitted arcs: Kay Kavus’s disastrous Mazandaran campaign and Rostam’s climactic rescue.

The White Demon is not a free-floating folkloric monster with many unrelated tales, but a tightly defined epic antagonist whose defeat completes a full cycle of collapse and restoration.

Religiously, his significance is indirect: the epic draws on Iranian demon terminology with deep roots in Zoroastrian thought, yet Div-e Sepid himself is not attested as a figure of ritual practice.

Interpreted rationally, the demon works as a high-intensity narrative instrument: he makes political hubris visible, concentrates danger into a single adversary, and allows the story to deliver a memorable reversal from blindness to recovered order.

Further Reading

DĪV (demon, monster, fiend)

Scholarly overview of the Iranian dīv/daēva concept across religious and literary traditions, explaining how “div” develops into a standard term for hostile supernatural beings in Persian narrative culture.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/div

Kay-Kavus (Shahnama story guide)

Museum learning page summarizing the Mazandaran campaign in the Shahnameh, including the White Demon’s blinding of Kay Kavus and the plot setup for Rostam’s rescue and final confrontation.

https://asia-archive.si.edu/learn/shahnama/kay-kavus/

Kay-Kavus Chained in a Cave (manuscript scene entry)

Object-focused museum entry describing the episode where the White Demon blinds and imprisons Kay Kavus, with context on Rostam’s arrival and the use of the demon’s blood to restore sight.

https://asia-archive.si.edu/learn/shahnama/f2006-7/

Rustam Slays the White Div, folio from a Shahnama

Museum collection record for an illustrated Shahnameh folio depicting Rustam’s battle with the White Div, useful as a verified visual anchor for how the episode is represented in art.

https://collections.lacma.org/node/237798

ŠĀH-NĀMA TRANSLATIONS iii. INTO ENGLISH

Reference survey of major English Shahnameh translations (including complete and abridged standards), useful for choosing a reliable translation base for Div-e Sepid passages and episode framing.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sah-nama-translations-iii-english

HAFT ḴᵛĀN

Clear scholarly overview of Rostam’s Seven Labors, including the final goal of killing Div-e Sepid and restoring Kay Kavus’s sight with the demon’s blood, plus narrative context.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/haft-kan/

MĀZAN

Scholarly entry explaining Mazandaran as a mythic landscape in the Shahnameh and discussing Div-e Sepid’s place in that episode, including notes on connections and limits versus Zoroastrian tradition.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mazan/

“Rustam Kills the White Div”, folio from a Shahnama (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Museum record describing the episode and its standard story framing, anchoring the cave battle and the rescue context in an accessible, verifiable curatorial summary.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/452632

Shahnama Project (Cambridge Digital Library collection)

Curated manuscript collection and episode indexing (including Mazandaran and the White Div material), useful for verifying what scenes are repeatedly preserved and how the tradition is transmitted visually.

https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/shahnama

How Rustam Killed White Div: An Interdisciplinary Inquiry, J. W. Clinton, 2006

Peer-reviewed study focused on the White Div fight and how text and illustration traditions converge on specific action beats, explaining why the scene stabilizes across manuscripts.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/iranian-studies/article/how-rustam-killed-white-div-an-interdisciplinary-inquiry/2C2E1B961377BC6F8F952AE6C7EC691B

NAQQĀLI, professional Iranian storytelling tradition of epic and religious narratives

Explains Iranian dramatic storytelling and its social role, including epic recitation as a vehicle for transmitting heroic cycles and memorable antagonists through performance rather than text alone.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/naqqali/

Naqqāli, Iranian dramatic story-telling (UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage)

UNESCO description of Naqqāli as a heritage practice, outlining how storytellers narrate verse and prose with gesture, music, and visual aids, sustaining Persian narrative culture across generations.

https://ich.unesco.org/en/USL/naqqli-iranian-dramatic-story-telling-00535

Rustam slaying the White Div (British Museum collection record)

Curatorial record of a Shahnama painting depicting Rustam attacking the White Div in a cave.

Useful for verifying the episode’s most repeated visual composition and manuscript tradition details.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1937-0710-0-327

AKVĀN-E DĪV, the demon Akvān, who was killed by Rostam

Scholarly entry summarizing Akvan-e Div’s Shahnama narrative function and traits, providing a reliable basis for comparing major div antagonists within the Rostam cycle.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/akvan-e-div-the-demon-akvan-who-was-killed-by-rostam/

AŽDAHĀ “dragon,” various kinds of snake-like, mostly gigantic, monsters

Detailed scholarly survey of Iranian dragon traditions and terminology, clarifying how monstrous “dragon” categories function across Iranian narrative and belief contexts.

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds/

Rakshasa | Hindu Myth, Demons, and Ravana

Concise reference describing rakshasas as mythological demons in Hindu tradition, including their disruptive role and association with key epic antagonists, supporting a function-based comparison.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/rakshasa

Jinni | Definition and Facts

Reference overview defining jinn as powerful, form-shifting spirits in Arabic mythology and Islam, useful for distinguishing “supernatural other” categories from Iranian div demon structures.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/jinni

Epic of Gilgamesh | Summary, Characters, and Facts

Overview of the Mesopotamian epic noting Humbaba as the divinely appointed guardian of the Cedar Forest, a clean parallel for “remote-zone guardian monster” story structure.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Epic-of-Gilgamesh

Shaitan | Jinn, Demons and Devils

Reference entry describing shaitan as an unbelieving class of jinn and a term for Iblis in demonic action, grounding a comparison to adversarial moral-force categories in mythic systems.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/shaitan

Zoroastrianism

Overview of Zoroastrian beliefs, including the religious opposition between order and destructive forces and how demon categories relate to ethical and ritual frameworks in Iranian tradition.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zoroastrianism

VENDIDAD (English), translated by James Darmesteter (Sacred Books of the East)

Primary-source translation of a Zoroastrian legal-ritual text focused on resisting pollution and hostile forces, useful for understanding how “daēva” functions as an anti-ritual category.

https://www.avesta.org/vendidad/vd_eng.pdf

AVESTA: VENDIDAD (English): Fargard 17 (Hair and nails; “offering to the Daevas”)

Concrete passage showing how misdeeds are conceptualized as strengthening daevas, illustrating the ethical-ritual polarity that later demon vocabulary inherits.

https://www.avesta.org/vendidad/vd17sbe.htm

Rostam’s Seven Trials and the Logic of Epic Narrative in the Shahnama

Academic analysis of how the Seven Labors function as an epic engine and why the White Demon episode works as a narrative climax in literary and folk transmission.

https://asianethnology.org/article/623/download

Wounded Bodies, Restored Realms (StoryPharm project, University of Cyprus)

Scholarly discussion of healing motifs in the Shahnameh, including the restoration of sight through the White Demon’s blood, useful for interpreting the blindness-and-repair mechanism.

https://www.ucy.ac.cy/storypharm/wounded-bodies-restored-realms/