Introduction

Kasa-obake, the one-legged, one-eyed umbrella spirit, has charmed and unnerved generations in Japanese folklore. Often considered mischievous rather than dangerous, Kasa-obake exemplifies the yōkai spirit, a unique blend of the whimsical and supernatural.

As one of the tsukumogami (household objects that become spirits after years of neglect), it holds a special place in Japanese culture, reflecting the idea that even mundane items can take on lives of their own. Today, Kasa-obake not only haunts the imaginations of folklorists but also holds a firm place in modern pop culture.

History/Origin

The origin of Kasa-obake can be traced back to the concept of tsukumogami in Japanese folklore, which emerged in the Heian period (794–1185). Tsukumogami are ordinary household items that gain a spirit if they exist for over a century without being discarded or cared for.

As industrialization increased and household items became more disposable, tales of tsukumogami like Kasa-obake gained traction, illustrating an awareness of wastefulness and the belief that neglected items could gain life.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), the popularity of yōkai and tsukumogami surged, with images of Kasa-obake appearing in art and literature. One notable depiction is seen in Toriyama Sekien’s “Gazu Hyakki Yagyō,” a famous yōkai encyclopedia from the late 18th century that popularized Kasa-obake among the urban Japanese populace.

Name Meaning

The name “Kasa-obake” directly translates to “umbrella ghost” or “umbrella monster.” In Japanese, “kasa” means umbrella, while “obake” or “bake” means ghost or spirit.

This name emphasizes Kasa-obake’s origins as an umbrella that has been forgotten and thus transformed into a supernatural being. The name is simple yet evocative, suggesting both its mundane beginnings and its ghostly transformation.

Appearance

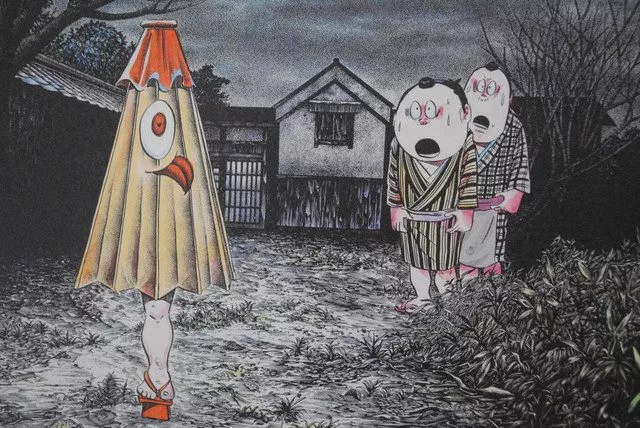

Kasa-obake is typically portrayed as a traditional Japanese umbrella with a single eye peering out from its canopy, a long red tongue lolling from the mouth area, and a single leg that it uses to hop around. Its skin has the worn, faded look of an old paper umbrella, often marked with stains and creases.

Some depictions also show it carrying a sandal, adding a humorous touch to its otherwise eerie appearance.

Sometimes, Kasa-obake appears with additional adornments, such as small torn sections or patched areas, indicating years of use. These details make it appear aged and endearing, but it’s the one-legged hop that gives it a comically frightening vibe.

The sight of a hopping, tongue-wagging umbrella can be both absurd and unsettling.

Background Story

Kasa-obake’s tale revolves around the idea that everyday objects may transform into yōkai if left unused or forgotten for long periods. In Japan, it’s believed that objects, especially those in close contact with humans, retain spiritual essence.

Over time, if discarded or neglected, this essence evolves, and the object becomes sentient, acquiring a personality based on its usage or abandonment. For Kasa-obake, this means emerging from the shadows to startle or play tricks on humans.

One popular story involves a traveler who encounters Kasa-obake on a rainy night. Thinking it’s merely an abandoned umbrella, the traveler picks it up, only for it to hop around, lick him with its exaggerated tongue, and disappear into the mist.

Such encounters typically end with a laugh, rather than terror, as Kasa-obake seldom poses a serious threat.

Cultural Impact

Kasa-obake, like many yōkai, mirrors the values and beliefs of traditional Japanese culture. It reminds people to respect their possessions, avoid wastefulness, and recognize the energy in everyday items.

Kasa-obake, though a creature of mischief, embodies the principle of mottainai, a Japanese term that encourages minimal waste and mindful use of resources. It reminds people that even simple items can have hidden value or spirits of their own.

In Japan, Kasa-obake also symbolizes a lighthearted approach to the supernatural. It’s a creature that children and adults alike can enjoy, providing laughter and a hint of mystery without invoking fear.

Kasa-obake’s enduring presence in Japanese stories, art, and celebrations like the Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons) shows how folklore can engage with both humor and reverence for life’s mysteries.

Similar Beasts

Kasa-obake is part of a larger family of tsukumogami. These include Chōchin-obake, a spirit of a paper lantern that comes to life, usually featuring a similar tongue and a single eye.

Another is Bakezōri, a sandal spirit that hops around, lamenting its fate as a forgotten item. These spirits share a common origin story of abandonment and remind people to value the mundane.

Another comparison can be drawn with Yurei, the ghosts of Japanese folklore. Unlike yurei, which are generally spirits of deceased humans, tsukumogami like Kasa-obake are objects given life.

However, both reflect a connection to the supernatural and the enduring presence of spirits in the natural world.

Religion/Ritual

While Kasa-obake is not deeply rooted in religious practice, its presence in Japanese culture highlights an animistic view where even objects have spirits. In some Shinto practices, old or broken objects receive purification rituals or are given a respectful farewell, reflecting the belief in honoring spirits within items, particularly those with longstanding use.

At certain festivals, such as the Hari Kuyo (Festival of Broken Needles), old tools and items are honored, acknowledging the spirit within. This practice connects to the idea of tsukumogami, where objects like Kasa-obake are respected, preventing them from becoming malevolent spirits.

Through these rituals, the Japanese show reverence for objects, reducing the likelihood of these items turning into mischievous beings.

Scientific or Rational Explanations

From a scientific perspective, Kasa-obake could symbolize how the human brain perceives faces and forms in inanimate objects, known as pareidolia. A worn umbrella might be seen as having eyes and a mouth, especially under eerie lighting, sparking stories of animated umbrellas.

Additionally, the concept of giving life to inanimate objects could stem from Japan’s traditionally strong belief in animism, the idea that all things contain spiritual energy.

Cultural anthropologists suggest that the concept of tsukumogami serves as a societal tool to encourage resourcefulness, mindfulness, and respect for objects. By embodying the idea of an umbrella coming to life, Kasa-obake discourages waste and inspires people to think twice before discarding items.

Modern Cultural References

Anime and Manga:

GeGeGe no Kitarō: This long-running series features numerous yōkai, including the Kasa-obake, often depicted as a mischievous character.

Video Games:

Yo-kai Watch: The game includes a character named “Kasa-obake,” directly inspired by the traditional yōkai.

Nioh: This action role-playing game features the Kasa-obake as an enemy, staying true to its folklore origins.

Literature:

The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore by Michael Dylan Foster: This book explores various yōkai, including the Kasa-obake, providing cultural context and historical background.

Film:

Yokai Monsters: 100 Monsters (1968): The Kasa-obake appears in this classic Japanese film, showcasing its traditional portrayal.

Conclusion

Kasa-obake, with its playful, harmless spirit, represents a lighter side of Japanese yōkai tradition. Rooted in the idea that even objects have souls, it serves as a reminder of respect for possessions, blending humor and folklore.

The enduring presence of Kasa-obake in Japanese culture shows how a simple concept, like an old umbrella coming to life, can inspire both fear and affection. As modern society continues to embrace sustainability, Kasa-obake remains relevant, urging a mindful appreciation for the items we use and discard.

Its popularity in contemporary media ensures that this quirky, hopping umbrella yōkai will continue to charm and amuse audiences worldwide, connecting us with Japan’s rich tradition of yōkai lore.