Lamashtu emerges as one of Mesopotamia’s most feared supernatural beings. People believed she hunted mothers and newborns, causing miscarriages, stillbirths and sudden infant death.

Her presence turned childbirth into a spiritual threat. She embodied dangers that felt unpredictable, intimate and impossible to ignore.

Communities created protective rituals because her influence seemed constant. Parents, midwives and healers faced the terror of losing children to forces they could not fully understand.

Through Lamashtu, they expressed grief and fear while shaping those emotions into a defined enemy they could confront through ritual action.

Her legend endures because she represents maternal vulnerability and the fragility of early life. She stands as a reminder of ancient struggles against sickness and mortality, and the belief that harmful beings walked invisibly beside families during their most dangerous moments.

History / Origin

Lamashtu appears in early second millennium BCE Mesopotamian ritual texts under the Sumerian name Dimme. Later Akkadian sources use the name Lamashtu.

These records present her as a consistent figure who threatens infants and pregnant women, showing her importance across shifting cultural and political landscapes.

Writers describe her as the daughter of Anu, which establishes her high status among supernatural beings. That lineage also strengthens her independence.

Unlike many malicious spirits who acted only when commanded, Lamashtu initiates harm by her own decision and targets families without divine instruction.

Exorcists developed a structured response to her. Tablets preserve ritual procedures involving offerings, figurines and repeated incantations meant to expel her.

These rituals guided healers as they worked to protect households from a demoness believed to attack sleep, pregnancy and early childhood.

Archaeologists uncovered amulets and plaques featuring her image in sites across Assyria, Babylonia and the Levant. Their frequency shows how deeply her presence entered daily life.

Ordinary families depended on protective objects to keep her away and reduce fears surrounding childbirth and infancy.

“Great is the daughter of Anu, who tortures babies and brings sorrow to households.” (Late Babylonian ritual text)

Name Meaning

The Akkadian form of her name appears as dLa-maš-tu, while her Sumerian form is Dimme. Both versions refer to the same powerful demoness.

Scholars debate the deeper linguistic roots, and no certain literal translation exists. Her name therefore functions primarily as a proper supernatural identity.

Ancient texts rarely attempt to define her name. They simply invoke it, suggesting all listeners already understood her role.

The fear associated with her name carried its meaning. Communities connected her identity with danger rather than with any etymological explanation of the word itself.

Over time commentators added interpretations, but ancient writers viewed Lamashtu as a being recognized by reputation. Her name represented an active threat to mothers and infants, shaped by centuries of stories, rituals and warnings repeated across Mesopotamian culture.

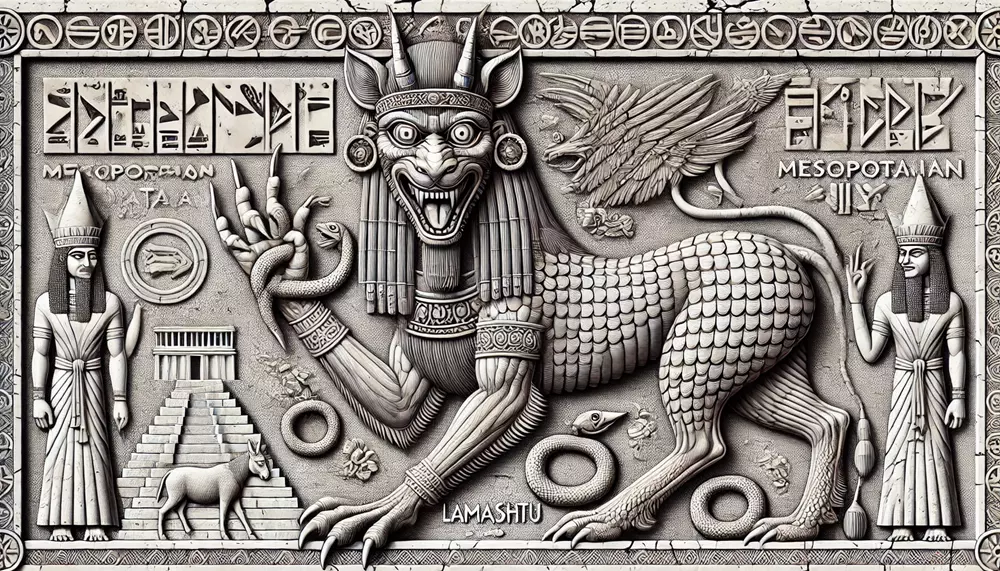

Appearance

Ritual texts and amulets describe Lamashtu with a lion’s head, donkey’s teeth, elongated fingers and nails shaped like claws. Her hairy body and monstrous proportions distinguish her from ordinary divine figures.

These features communicate predatory strength and the unnatural nature of her attacks.

Artists sometimes gave her birdlike talons or the feet of the storm creature Anzû. She often carries serpents in her hands and nurses wild animals such as dogs or pigs, symbolizing a twisted inversion of motherhood.

Her hybrid form reflects her role as a destroyer of children and families.

“Her head is a lion’s head, her teeth are donkey’s teeth, her hands are stained with blood.” (Akkadian incantation describing Lamashtu)

Amulets portraying her often include inscriptions that bind or restrain her. Families placed these near cradles or beds to force the demoness to obey protective commands.

Her terrifying image therefore served a dual purpose as both a warning and a shield.

Background Story

Lamashtu’s story appears across many short ritual texts rather than in long narrative epics. These spells depict her as an autonomous demoness who chooses her victims.

She roams through houses at night, targeting pregnant women and newborns, bringing miscarriage, fever and sudden infant death.

One well known line shows her aggression clearly.

“She touches the pregnant woman’s belly, she pulls out the baby, she seizes the newborn from its mother.” (Old Babylonian Lamashtu incantation)

Her attacks helped families explain tragedies they struggled to understand. Illness, miscarriage or unexplained death became signs of her presence.

Rituals offered a structured way to respond, giving communities emotional and spiritual tools to resist her destructive influence.

Pazuzu appears as her chief adversary. Although feared, he protects mothers by driving her away. Families used Pazuzu amulets to guard doorways and sleeping places.

His hostile nature works in their favor, turning one dangerous being into a protector against an even greater threat.

“Pazuzu, son of Hanpa, restrains her steps and turns her away from the dwelling of the mother.” (Pazuzu protective inscription)

Exorcists performed rituals involving figurines and incantations to force Lamashtu from a household. They symbolically expelled her through water or burial.

These acts reestablished order by confronting the demoness directly and reinforcing community control over harmful supernatural forces.

Famous Folklore Stories

The Cradle Snatcher

Folklore described Lamashtu entering quiet homes after nightfall to seek unprotected infants. Families believed she moved through shadows and open doorways, targeting cradles lacking charms or ritual defenses.

This story explained sudden infant loss among households that feared supernatural intrusion.

Families placed protective objects near their children to warn or repel her. The story emphasized constant vigilance, teaching that a forgotten charm or unattended cradle invited danger and transformed a peaceful night into a moment of terror.

The Poisoned Waters Legend

Another traditional story claimed Lamashtu wandered riverbanks and marshlands, spreading sickness through tainted water sources. People believed she carried fever and disease, leaving illness wherever she walked.

This tale helped communities explain outbreaks that began near fields, wells or shared water points.

Folklore warned travelers to avoid unfamiliar water at dawn or dusk, when spirits shifted between realms. Families purified stored water through ritual acts, believing these protections guarded the household against unseen contamination carried by the demoness.

The Seven Witches’ Midwife Curse

A well known folkloric tradition claimed Lamashtu once served as midwife to the Seven Witches, a feared group of destructive spirits. After assisting them, she turned against human families.

This story explained her relentless hostility toward childbirth and her desire to harm infants.

Communities viewed this tale as the origin of her enduring hatred. It justified the elaborate rituals performed during labor, which families believed protected newborns and mothers from the ancient curse tied to her service among the destructive spirits.

Cultural Impact

Lamashtu shaped how ancient Mesopotamians understood the risks of pregnancy and infancy. Families saw her behind sudden miscarriages and unexplained deaths.

This belief influenced daily choices, from where women slept to which charms they wore, as they tried to keep danger at a distance.

Archaeological finds of Lamashtu plaques and amulets across Assyria and Babylonia show how common this fear was. These objects appear in ordinary homes, not only palaces or temples.

Their distribution reveals that concern about her attacks cut across social classes and regions.

Her image also structured the work of exorcists and healers. Entire ritual series teach specialists how to diagnose her presence and counter it.

Through Lamashtu, ritual experts claimed authority over invisible threats, strengthening their social position within communities that depended on their protection.

Later demonological traditions in the Near East, and eventually in Mediterranean cultures, reused themes similar to Lamashtu, such as child snatching and dangerous night spirits. Even when her name disappeared, echoes of her role survived within broader ideas about hostile beings that haunt birth and early childhood.

Similar Beasts

Lilith

Lilith appears in later Jewish tradition as a night demon who targets infants and pregnant women. Like Lamashtu, she symbolizes female associated supernatural danger around childbirth.

Both figures connect sexuality, motherhood and fear, though Lilith belongs to a different cultural and chronological context.

Abyzou

Abyzou, known from later Near Eastern and Byzantine traditions, also attacks children and causes miscarriages. Scholars often see her as influenced by earlier Mesopotamian ideas.

Parallels with Lamashtu include association with disease, envy of mothers and a role as explanation for infant mortality.

Lamia

In Greek tradition, Lamia devours children and lures men to destruction. Her myth centers on stolen offspring and transformed female rage.

Although culturally distant, she resembles Lamashtu in combining monstrous features, threats to young life and a narrative shaped around maternal suffering and revenge.

Gello

Gello, a child harming spirit in Greek and Byzantine folklore, stalks newborns and women in childbirth. Like Lamashtu, she does not require divine command to act.

Protective amulets and prayers developed around both figures, showing similar responses to perceived supernatural causes of infant death.

Alu

Alu, a Mesopotamian night demon, brings sleeplessness and terror. Unlike Lamashtu, Alu does not focus specifically on childbirth, yet both belong to a broader class of entities blamed for illness and nocturnal distress.

Together they illustrate how people personalized unexplained suffering through demonic figures.

Religion / Ritual

Lamashtu stood at the center of many household level religious practices. Families feared her arrival more than distant cosmic crises.

Religious concern focused on protecting pregnant women and infants, because birth represented a critical threshold where divine, demonic and human realms intersected directly.

Exorcists and ritual specialists developed elaborate ceremonies to confront her. These rites involved figurines, offerings, water rituals and spoken formulas.

Practitioners followed detailed instructions, repeating actions over several days. The structure of these rituals reflects a belief that persistent, orderly practice could reestablish safety and drive her away.

Household religion integrated these rituals into ordinary life. Parents placed protective items near beds, hung images of Pazuzu, or buried inscribed objects under thresholds.

Such acts expressed faith that the divine world listened and responded, and that correct ritual behavior could shield vulnerable family members from harm.

Temple based religion also acknowledged Lamashtu indirectly through wider concern for purity, health and divine favor. Offerings to major deities could accompany private anti Lamashtu rituals, creating a layered approach where great gods received worship while specific demons received targeted defensive attention.

Scientific or Rational Explanations

Modern scholars interpret Lamashtu as a personification of very real dangers faced in ancient societies. High rates of maternal mortality, miscarriages and infant deaths demanded explanations.

By picturing these tragedies as the work of a specific being, communities found a way to describe and emotionally manage their fears.

From a medical perspective, many conditions now associated with infection, hemorrhage, prematurity or genetic disorders likely informed her legend. Without knowledge of germs or physiology, people saw patterns linking symptoms to times, places or life stages, and attributed them to Lamashtu’s presence, especially around childbirth and early infancy.

Psychologically, the figure of Lamashtu externalized guilt and anxiety. Parents who lost children could blame a demon instead of themselves or relatives.

This helped preserve social bonds and personal stability, even if the underlying physical causes remained unknown. Myth and ritual functioned as emotional survival tools.

Anthropologically, Lamashtu illustrates how societies convert chaotic suffering into structured belief and practice. Her image, rituals and stories form a system that turns unpredictable events into something people can discuss, plan for and symbolically resist, even when they lack the means to control the biological realities involved.

Modern Cultural References

Lamashtu appears as a major deity and demon lord in the Pathfinder roleplaying game setting, described as Mother of Monsters and Mistress of Insanity. Official game rules present her as a goddess worshipped by monstrous cults.

Reference example: https://2e.aonprd.com/Deities.aspx?ID=11

In the psychological horror film Still Born from 2017, Lamashtu serves as the supernatural force threatening a new mother and her surviving child. Reviews and plot summaries identify her explicitly as a Mesopotamian infant stealing demon.

Film reference: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6087426/

The 2018 black metal album Mark of the Necrogram by Necrophobic includes a track titled Lamashtu. Album listings and reviews confirm this song references the ancient demoness within an extreme metal aesthetic.

Music reference: https://www.metal-archives.com/albums/Necrophobic/Mark_of_the_Necrogram/756337

In the television series Constantine, Lamashtu appears in the episode The Saint of Last Resorts. She is depicted as a child abducting demon opposed by John Constantine, with Pazuzu also involved.

Reference example for the character: https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/Lamashtu_(Arrowverse)

The 2023 horror film The Exorcist Believer presents Lamashtu as the possessing entity behind the central exorcism case, explicitly naming her in credits and promotional material. Film reference: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt12921446/

Conclusion

Lamashtu brings together religious fear, medical uncertainty and narrative imagination. For ancient Mesopotamians she explained some of the most painful experiences a family could endure.

Her figure concentrated anxieties about pregnancy, birth and infant survival into one recognizable, if terrifying, supernatural presence.

Through rituals and amulets, communities responded actively to that presence. People did not simply resign themselves to fate.

They attempted to push back using the tools available to them, which included spoken formulas, offerings, images and carefully structured ceremonies designed to keep her away from homes and cradles.

Comparisons with similar figures such as Lilith, Abyzou and Lamia show that the idea of female associated child harming spirits recurred across cultures and centuries. Lamashtu stands as one of the earliest and most detailed examples, revealing the deep historical roots of these enduring supernatural themes.

Her survival in modern games, films and music demonstrates the continuing power of ancient myths and demonologies. Contemporary creators rediscover Lamashtu as a symbol of distorted motherhood, monstrous birth and predatory fear, proving that stories born from ancient grief still resonate in new cultural forms today.

Further Reading

Mesopotamian Magic in the First Millennium BCE – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

An academic exploration of magical practices, including Lamashtu rituals, amulets and household protective traditions in ancient Mesopotamia.

https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/mesopotamian-magic-in-the-first-millennium-bc

Lamashtu – Britannica

Concise summary of Lamashtu’s character, origins and impact within Mesopotamian demonology and protective ritual traditions.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lamashtu

Demons and Exorcism in Ancient Mesopotamia – ResearchGate Publication

Scholarly analysis of Mesopotamian demonology and exorcistic traditions, discussing Lamashtu within broader ritual contexts.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344194259_Demons_and_exorcism_in_ancient_Mesopotamia

Lamashtu compared to Lilith, Lamia, and Gello

| Aspect | Lamashtu | Lilith | Lamia | Gello |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Lamashtu originates from Sumerian and Akkadian texts, highlighting her ancient roots. | Lilith is often associated with Jewish folklore and mythology, representing a different cultural background. | Lamia's origins are rooted in Greek mythology, where she is depicted as a tragic figure. | Gello is a figure from Greek mythology, known for her malevolent nature and origins. |

| Appearance | Lamashtu has a lioness-like head, sharp claws, and birdlike talons, creating a fearsome image. | Lilith is often depicted as a beautiful woman with long hair, symbolizing seduction and danger. | Lamia is described as having a serpent-like lower body, emphasizing her monstrous nature. | Gello is portrayed as a woman with a terrifying appearance, often associated with death. |

| Victims | Lamashtu primarily targets mothers and infants, causing illness and death among the vulnerable. | Lilith is said to prey on newborns and men, representing a threat to family life. | Lamia is known for consuming children, reflecting her role as a predator in mythology. | Gello is believed to harm infants and pregnant women, similar to other mythological figures. |

| Powers | Lamashtu possesses the power to spread disease and darkness, embodying chaos and fear. | Lilith is often associated with seduction and the ability to cause harm through her allure. | Lamia has the power to enchant and devour, using her beauty as a weapon. | Gello is known for her ability to inflict harm on mothers and their children. |

| Cultural Impact | Lamashtu's image has influenced various protective rituals and talismans throughout history. | Lilith has inspired numerous works of art and literature, symbolizing female empowerment and danger. | Lamia's story has been retold in various literary forms, emphasizing her tragic nature. | Gello's presence in folklore has led to cautionary tales about motherhood and protection. |

| Protection Methods | People used rituals and talismans to ward off Lamashtu's evil influence in ancient times. | Lilith is often invoked in protective charms to safeguard against her perceived threats. | Lamia's myth has led to protective measures for children in ancient cultures. | Gello's legend prompted various protective practices to shield mothers and infants from harm. |