Introduction

Samael is a named angelic figure in Jewish tradition whose profile shifts depending on the corpus you are reading. In some strands of rabbinic and midrashic literature, he appears as a prosecutor in the heavenly court, a seducer/instigator, and a destructive emissary who executes harsh decrees.

In later Jewish mystical writing, especially Kabbalah, he becomes a more systematized symbol of the “other side” of reality, associated with demonic forces while still framed as operating within divine sovereignty.

Two points must stay explicit to keep this accurate. First, “Samael” is not a single, stable character across time.

The tradition stacks layers: targumic and midrashic motifs (accusation, temptation, death) sit beside Kabbalistic metaphysics (other side, demonic hierarchy, cosmic balance). Second, many popular descriptions mix these layers into one “character sheet.”

This article will not. Each claim is tied to a specific textual stratum: rabbinic/midrashic versus Kabbalistic versus later reception.

History/Origin

Early textual footprint: rabbinic and targumic layers

The name “Samael” becomes prominent in post-biblical Jewish literature, where the tradition assigns him overlapping functions: accuser, instigator, and destroyer. Some late interpretive traditions explicitly connect him with the angel of death motif, including the image of death delivered through poison, a theme that appears in rabbinic discussion of the death-angel’s method.

Other streams treat “Samael” as a personal name for a satanic prosecutor figure, while “satan” remains a functional title in the broader literature.

Midrashic expansion: Eden and the serpent-rider motif

A major narrative intensification appears in midrashic material, where Samael is cast as a leading adversarial power who descends to influence humanity. One influential thread links him to the Eden story not by rewriting the biblical text directly, but by layering an interpretive narrative in which he is associated with the serpent’s temptation.

In this tradition, Samael is portrayed as the instigator behind the seduction, often using the serpent as his vehicle or agent. This is an interpretive motif with a specific textual home; it should not be presented as the plain meaning of Genesis.

Kabbalistic systematization: evil, the “other side,” and paired myth

In medieval Kabbalah, Samael is no longer only a narrative antagonist. He becomes a structured symbol inside a cosmology, connected to the realm of impurity often called the “other side.”

This is also where the tradition most explicitly develops Samael’s relationship with Lilith as a paired mythic configuration, framing them as a demonic couple within a broader metaphysical architecture. Scholarship on early Kabbalah treats this pairing as a distinct development rather than a simple continuation of earlier rabbinic depictions.

Name Meaning

Etymology in Hebrew sources

“Samael” (סַמָּאֵל) is most commonly explained as a compound of sam (סם, “drug/poison”) plus El (אֵל, “God”). In this reading, the name is understood as “poison of God” or “venom of God,” a label that matches later Jewish descriptions of an angelic agent associated with lethal decree and the “poison-drop” motif used for the angel of death.

What the name signals in tradition

In Jewish textual culture, angel names often function like role-labels rather than personal biographies. “Samael” reads as a title that encodes function: a divine agent whose work is harsh, dangerous, or judicial.

Importantly, the etymology does not automatically prove a single, fixed identity across all corpora. It explains why later writers found the name fitting for traditions linking Samael with death, accusation, and destructive force.

Appearance

Rabbinic Context: Angelic Status Without Fixed Iconography

In early rabbinic literature, Samael does not have a standardized physical description. He is treated as an angelic figure of rank and authority rather than as a creature with fixed visual traits.

The emphasis is hierarchical, not anatomical. When imagery appears, it follows broader angelological language found in apocalyptic and mystical traditions.

Samael is described as a “great prince in heaven,” indicating status within the celestial court rather than a monstrous form. Unlike later demonological portrayals, early sources do not present him with horns, grotesque features, or corrupted anatomy.

His depiction remains within the framework of angelic beings.

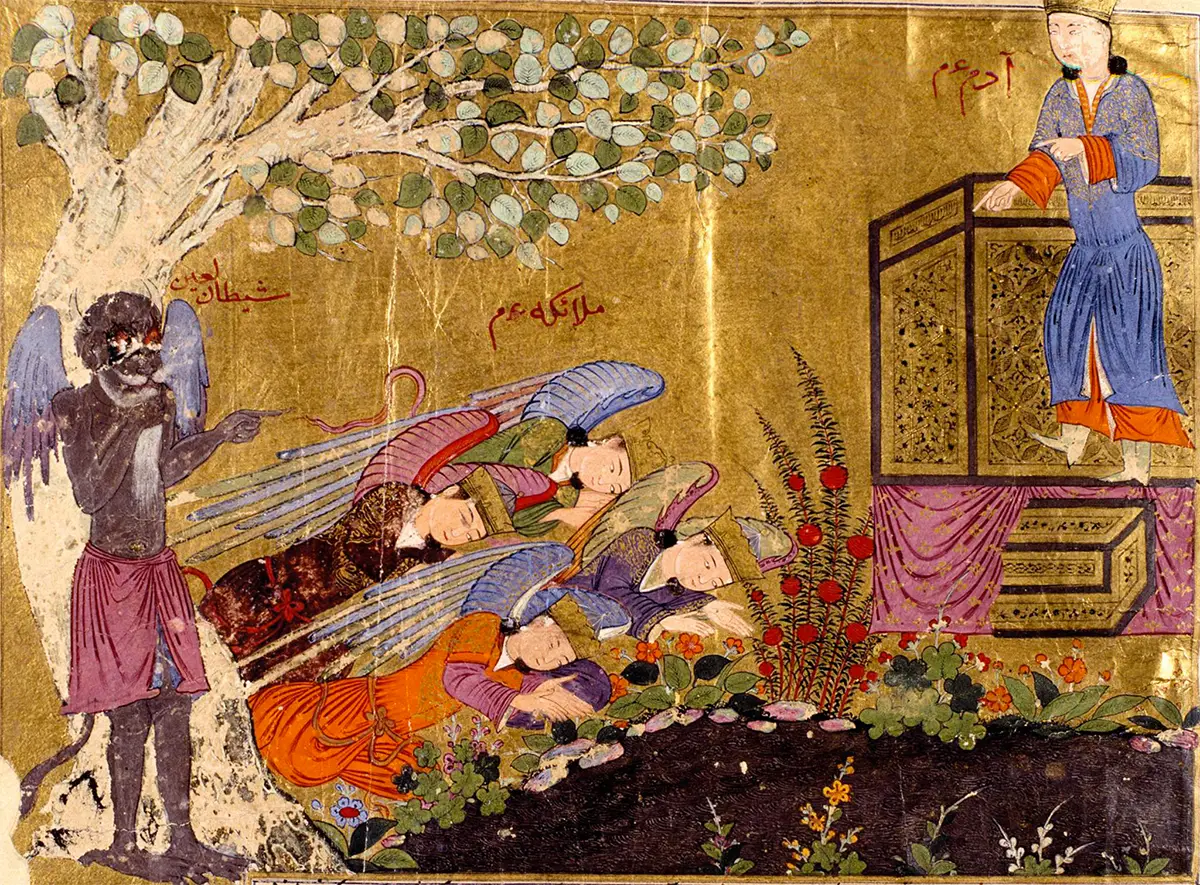

Midrashic Wing Imagery (Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer)

One of the clearest early visual descriptions appears in Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer (chapter 13), where Samael’s rank is emphasized through symbolic wing imagery:

“And Samael was a great prince in heaven; the living creatures had four wings, and the seraphim had six wings, but Samael had twelve wings.” (Midrash, Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, Chapter 13)

This passage does not aim to describe literal anatomy. In Jewish apocalyptic symbolism, wings represent spiritual capacity and proximity to divine power.

The comparison establishes Samael as an exalted and formidable angelic being within that narrative layer. It signals authority and intensity, not monstrosity.

Association with the Serpent Motif

Later midrashic expansions connect Samael to the serpent in Eden. Some traditions describe him as acting through or riding upon the serpent during the temptation of Eve.

This association introduces serpentine symbolism into his visual identity.

However, the serpent form is narrative and situational. The texts do not describe Samael as permanently serpentine in essence.

The serpent functions as an instrument within a theological story about temptation and moral testing.

Kabbalistic Symbolism: Severity and the “Other Side”

In medieval Kabbalah, Samael’s imagery becomes more abstract and metaphysical. He is associated with the realm sometimes called the “other side,” representing severity, judgment, and destructive force within divine order.

Descriptions in mystical literature may emphasize fire, shadow, or fearsome authority, but these are symbolic expressions of metaphysical qualities. They should not be read as fixed physical traits.

Even in these texts, Samael remains under divine sovereignty rather than existing as an independent cosmic rival.

Later Artistic and Cultural Developments

Medieval Jewish art does not preserve a stable iconographic tradition for Samael. In later Christian and occult reinterpretations, however, he is sometimes depicted with dark wings, serpentine elements, or demonic features.

These portrayals reflect cross-cultural evolution and should not be projected backward onto earlier Jewish sources.

Modern fantasy and occult imagery often exaggerate these later developments, presenting Samael as a towering fallen angel or demonic commander. Such depictions belong to reception history rather than classical Jewish textual tradition.

Background Story

The world that needed a figure like Samael

Samael’s motif is born in a Jewish intellectual climate that wanted precision about power. Late antique Jewish theology increasingly spoke in the language of courts, ranks, and delegated functions: accusation, opposition, punishment, and the boundary of life and death.

In that framework, the hardest forces in human experience could be narrated without collapsing into two gods or random fate. A figure like Samael becomes useful because he can embody the pressure of judgment and the reality of temptation while still remaining inside a cosmos governed by one sovereign will.

How a role becomes a name

Early biblical language often treats “the satan” as an office, an adversarial function that can appear when the story requires prosecution or obstruction. Over time, post-biblical storytelling begins to stabilize these functions into named personalities.

Samael becomes one of the most durable names for that adversarial profile. This is the moment the myth truly “begins” in the literary sense: the tradition is no longer only describing an adversarial mechanism, it is collecting themes into a recognizable character who can be placed into scenes, assigned motivations, and developed across genres.

Why Eden becomes the catalyst

Interpretation of Genesis becomes the strongest engine for myth-growth. Eden is the primal stage where desire, prohibition, and consequence first collide, so later writers return to it to explain how moral failure feels both intimate and intelligent.

In that interpretive move, Samael becomes a narrative key: the temptation is no longer just an animal speaking, but a higher adversarial will acting through a vehicle. That shift does not replace Scripture; it builds a theological “behind the curtain” layer that makes temptation legible as strategy, not accident.

When myth turns into system

Medieval Jewish mysticism takes what earlier texts scattered across stories and reorganizes it into architecture. Samael’s role becomes legible inside a mapped cosmos of opposing forces, where severity has structure and the “shadow-side” is given vocabulary, hierarchy, and internal logic.

This stage matters because it transforms a flexible adversarial figure into a stable component in a metaphysical model, and later reception will often inherit that stability even when it forgets the earlier layers that made it possible.

Famous Stories

Eden: the adversary chooses a vessel

In the Eden expansion, Samael enters as a high-ranking heavenly power whose presence is felt before he even acts. The narrative does not linger on spectacle for its own sake; it uses grandeur to establish danger.

Then it becomes almost practical: Samael seeks a method, surveys creation for the best instrument, and converges on the serpent as the perfect carrier for persuasion. The story’s drama is not warfare but infiltration: it explains why temptation speaks in a voice that sounds plausible, intimate, and just one step away from obedience.

Jacob at night: a struggle that becomes identity

The wrestling scene begins in darkness and ambiguity, because its purpose is transformation. Classical interpretation reads the attacker as more than a stranger: the struggle becomes a confrontation with the spiritual power behind Esau.

Later mystical reception sharpens the adversary’s identity further by linking the scene to Samael.

Across layers, the constant is the structure of the myth: the opponent cannot simply destroy Jacob, but can wound him; Jacob cannot simply escape, but must endure. Dawn arrives, the conflict releases, and the outcome is not triumph alone but a new name, a new posture, and a permanent mark.

Moses at the edge of death: the emissary meets a boundary

Traditions about Moses’ final hours stage the approach of death as a confrontation, because Moses’ stature demands a witness. The Angel of Death enters not as a random terror but as a deputized force, sometimes explicitly named Samael in expanded versions.

The scene turns on reversal: the feared emissary approaches, yet recoils; Moses is not merely passive, but aware, resisting, forcing the narrative to acknowledge that even a destructive power has limits. The myth’s point is boundary and hierarchy: death is real, but it is not sovereign.

Cultural Impact

Jewish mysticism and the shaping of a durable archetype

Samael’s largest cultural footprint is inside Jewish mystical imagination, where he becomes a stable symbol for severity, accusation, and the shadow-side of judgment. Once a figure can hold multiple roles across genres, later writers use the name as a shorthand for a specific emotional and theological register: fear that feels lawful, danger that feels sanctioned, temptation that feels intelligent.

This is why Samael remains memorable even when individual stories vary.

Cross-tradition drift and later rebranding

Outside Jewish textual culture, Samael’s image often migrates into broader “dark angel” or demonological palettes. In Christian and occult reception, the name is frequently treated less as a layered Jewish figure and more as an emblem of rebellion, forbidden knowledge, or infernal authority.

That shift is a reception effect: the name becomes portable, detachable from its original textual constraints, and reusable as a brand of cosmic menace.

Modern creative and subcultural usage

In modern literature, music, and gaming-adjacent culture, Samael functions as a ready-made label for morally complex darkness. Creators reach for it because it signals an ancient pedigree without requiring a single canonical storyline.

The result is a character-name that can be deployed as angelic, demonic, or ambiguous, depending on the genre’s needs.

Scientific or Rational Explanations

Personifying death and moral consequence

A rational lens treats Samael as a narrative technology for coping with two universal pressures: death and accountability. By personifying lethal decree and moral testing, the tradition converts abstract fear into a structured relationship.

Death becomes an encounter with an agent, and ethical failure becomes prosecutable rather than random. This makes the world feel more legible, even when it remains frightening.

Theodicy without dualism

Samael also fits a recurring monotheistic challenge: how to describe harsh forces without creating a rival god. Angelic intermediaries allow a community to speak about destruction, temptation, and accusation as functions within a governed cosmos, not as independent metaphysical powers.

The myth preserves divine sovereignty while still giving language to darkness.

Social function: boundary enforcement and risk education

On a social level, adversarial angels help communities teach boundaries: what not to do, what not to desire, what to fear, and how to interpret suffering. The motif reinforces communal norms by making moral drift feel consequential, watched, and legally framed.

In that sense, Samael operates as an imaginative enforcement mechanism inside a broader ethical system.

Similar Beasts

Azrael

Azrael is Islam’s angel of death, who separates souls from bodies at God’s command. He acts as a psychopomp, emphasizing duty and order rather than rebellion, in Islamic eschatological tradition.

Like Samael, he personifies mortality within monotheism. Unlike Samael’s later Jewish roles as accuser and tempter, Azrael is largely nonjudgmental, executing timing without prosecuting human choices or provoking moral tests.

Iblis

Iblis is the Qur’anic figure who refuses to bow to Adam, is cast out, and becomes a leading tempter. He embodies pride, refusal, and ongoing seduction of humans across history.

He parallels Samael where temptation is purposeful and personal. Yet Samael can appear as a heavenly prosecutor within Jewish angelology, while Iblis is consistently the paradigmatic rebel and deceiver there.

Anubis

Anubis is the ancient Egyptian god of funerary practice, mummification, and care for the dead, portrayed as a jackal or jackal-headed man guiding bodies toward afterlife rites and protecting tombs.

He resembles Samael in linking divine authority to death’s threshold. But Anubis is principally protective and ritual, whereas Samael’s Jewish portrayals foreground accusation, temptation, and punitive force in narrative scenes.

Charon

Charon is Greek mythology’s ferryman of the dead, carrying souls across Styx or Acheron when burial rites are complete. Payment imagery, the coin, anchors death as passage into Hades’ domain.

He parallels Samael as a boundary-agent between worlds. Yet Charon is transactional and impersonal, while Samael’s traditions often dramatize moral testing, prosecution, and resistance in confrontations within divine courtroom imagery.

Hel

Hel in Norse tradition rules a realm of the dead, later personified as a goddess, tied to cold, darkness, and inevitability. She receives those who do not die in battle.

She resembles Samael by embodying death’s jurisdiction rather than random violence. Unlike Samael’s accusatory and temptational functions, Hel is chiefly a sovereign custodian, governing place and fate without prosecuting sin.

Samael in Islamic Tradition

Name-status: absent from Qur’an and mainstream Hadith naming

In normative Islamic scripture, Samael is not a standard named figure. The Qur’an does not present an angel called Samael, and mainstream Islamic teaching typically avoids importing extra-biblical angel names unless supported by strong transmission.

When “Samael” appears in modern Muslim Q&A spaces, it is usually treated as a non-canonical name from other traditions rather than an Islamic one.

The Angel of Death: a Qur’anic role, later a conventional name

Islamic tradition clearly affirms an Angel of Death as a role. The Qur’an speaks about “the Angel of Death” assigned over people, without providing a personal name.

Later exegetical and narrative literature commonly uses the name ʿIzrāʾīl / ʿAzrāʾīl for this angel, and some tafsir materials explicitly mention that name as a known report.

This is the important precision point for your article: in Islam, the function is scriptural, while the name “Azrael/Izra’il” is a later convention in tafsir and popular tradition, not a Qur’anic proper noun.

Temptation and rebellion: Iblis, not Samael

Where Jewish tradition can layer Samael into Eden expansions, Islam places the primal rebellion and ongoing temptation primarily with Iblis. The Qur’an describes the command to bow to Adam, Iblis’s refusal, and his arrogance.

This becomes the backbone for Islamic moral psychology around temptation: a clear, named tempter figure whose narrative role is central and consistent.

In Modern Culture

Samael’s presence in modern pop culture is a testament to his timeless appeal as a character who’s both intimidating and morally complex. From literature to video games, Samael continues to inspire creators who want to explore themes of duality, temptation, and redemption.

Lucifer, “Favorite Son” (TV episode, 2016)

In this episode, Dr. Linda explicitly tells Lucifer that before his fall he was known as “Samael,” and Lucifer replies that he doesn’t use that name anymore.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4952858/

Hellboy (film, 2004)

The film features a hell-hound antagonist named Sammael (“the Desolate One”). It’s a modern name-reuse, not a claim of Jewish-text accuracy, but the name is explicitly used on-screen.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0167190/

Darksiders (video game, 2010)

The official game manual describes Samael as a once-mighty, feared demon now imprisoned after rising against the Destroyer, and states War must seek his aid to reach the enemy.

https://manuals.thqnordic.com/Darksiders/Darksiders_PC_Manual_EN.pdf

Darksiders II, “Samael” boss encounter (video game, 2012)

The game includes a titled boss fight against Samael, presented as a major demonic power with teleportation and high-tier combat mechanics, reinforcing him as a central franchise figure. (Gamepressure.com)

https://www.gamepressure.com/darksidersii/boss-19-samael/z94023

Shin Megami Tensei V: Vengeance (video game, 2024)

Samael appears as a demon in SMT V: Vengeance, covered in official-style “Daily Demon” spotlight reporting and compendium references, treating him as a named entity within the franchise’s demon roster.

https://personacentral.com/smt-vv-daily-demon-75/

Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne HD Remaster (video game, 2021)

Samael is listed as a recruitable/fusable demon with defined race/alignment and stats in Nocturne HD, reflecting the series’ long-running use of Samael as a named demon figure.

https://samurai-gamers.com/shin-megami-tensei-iii-nocturne-hd-remaster/samael-demon-stats-and-skills/

Samael (music band, Switzerland, active since late 1980s)

The Swiss metal band “Samael” is a verified modern use of the name as an identity marker in music culture, separate from religious texts and used as a dark, mythic signifier. (IMDb)

https://www.metal-archives.com/bands/Samael/31

Further Reading

Samael (Jewish Encyclopedia), Isidore Singer (ed.), 1906

A classic reference overview: Samael as accuser, seducer, destroyer; later identifications with the angel of death; notes key rabbinic and post-rabbinic sources and motifs. https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13055-samael

Samael (Jewish Virtual Library), editors of Jewish Virtual Library.

Concise synthesis of Samael’s roles across rabbinic, midrashic, and mystical traditions, including how later Jewish writings connect him with Satanic and death-angel functions. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/samael

Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer 13, traditional midrash (Sefaria)

Primary source where Samael is depicted with expanded adversarial/temptation functions; includes the motif of Samael acting through the serpent in the Eden narrative layer.

https://www.sefaria.org/Pirkei_DeRabbi_Eliezer.13

Samael on topic hub (Sefaria),

Curated gateway to primary texts across corpora that mention Samael, allowing direct verification of claims by tradition layer instead of relying on paraphrase or modern summaries.

https://www.sefaria.org/topics/samael

Samael, Lilith, and the Concept of Evil in Early Kabbalah, Joseph Dan, 1980

Peer-reviewed study of how early Kabbalah develops the mythic structure of evil and the Samael-Lilith pairing, clarifying what is new in medieval Kabbalah versus earlier sources.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/samael-lilith-and-the-concept-of-evil-in-early-kabbalah/E9CBB1BD77735680204FCB44C0C92A19

Lilith (Jewish Women’s Archive Encyclopedia).

Explains Lilith’s evolution and explicitly discusses later mystical developments connecting Lilith with Samael and the “other side” concept, with a focus on textual tradition rather than pop-myth.

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/lilith

Cain, Son of the Fallen Angel Samael, TheTorah.com.

Scholarly-style discussion focused on how Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer builds the Eden/Samael motif and its implications; useful for cleanly separating midrashic expansion from biblical narrative.

https://www.thetorah.com/article/cain-son-of-the-fallen-angel-samael

Samael | Description, Judaism, Satan, Lilith, History, & Facts (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

High-quality synthesis that distinguishes midrashic developments from broader Jewish tradition, explicitly noting Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer’s role in expanding Samael’s adversarial profile and myth growth.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Samael

A Rabbinic Traditions-History of the Samael Story in “Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer” (JSTOR), Ryan S. Dulkin, 2014

Peer-reviewed article tracing how Samael’s Eden-related narrative evolves within Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer, clarifying what is new, what is reused, and how the tradition expands over time.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24751800

Rabbinization of Non-Rabbinic Material in Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer (Open Book Publishers),

Academic chapter discussing how Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer adapts and reshapes earlier material, useful context for understanding why Samael’s narrative role grows in this work’s Eden-focused passages.

https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0219/ch13.xhtml

The Devil Within: A Rabbinic Traditions-History of the Samael Story in Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, Ryan S. Dulkin, 2014

Peer-reviewed traditions-history mapping how Samael’s Eden motif evolves across versions and redactional layers, separating earlier narrative kernels from later expansions and clarifying what each layer is doing.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24751800

Defying Death: Abraham and Moses in Jewish Antiquity, David J. Zucker

Academic article that discusses Moses-and-death-angel traditions, including Deuteronomy Rabbah material, and explains how these narratives dramatize authority, resistance, and the boundaries of angelic power.

https://place.asburyseminary.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2636&context=asburyjournal

Be Thyself (Vayishlach) Beit Midrash, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

A careful interpretive discussion of Jacob’s wrestling episode and its major identifications in Jewish tradition, framing the struggle as spiritual confrontation and identity-formation rather than mere physical conflict.

https://www.yeshiva.co/midrash/45864

Satan (The Jewish Agency / Jewish Ideas and Ideals portal)

Clear overview of how “satan” operates as role and concept in Jewish tradition, helpful for separating functional adversary language from later named personifications like Samael.

https://www.jewishagency.org/jewish-ideas/satan/

Satan and the Problem of Evil (My Jewish Learning)

Explains how Jewish thought navigates evil, accusation, and divine justice without dualism, providing context for why intermediary figures develop and persist.

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/satan-the-adversary/

Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 1941

Foundational scholarly work explaining how medieval Jewish mysticism systematizes spiritual forces and symbols, useful for understanding how figures like Samael gain structured cultural power.

https://archive.org/details/majortrendsinjew00scho

Moshe Idel, Kabbalah: New Perspectives, 1988

Academic framework for reading Kabbalistic symbolism as a cultural system, clarifying how mythic figures function across texts, schools, and historical contexts.

https://archive.org/details/kabbalahnewpersp00idel

Alan F. Segal, Two Powers in Heaven, 1977

Classic study on Jewish discourse about divine agency and intermediaries, valuable for a rational explanation of why traditions develop complex angelic roles while resisting dualism.

https://archive.org/details/twopowersinheave00sega

Qur’an 32:11 (As-Sajdah) – “Angel of Death” verse.

Canonical Qur’anic wording that explicitly mentions “the Angel of Death… assigned to you,” establishing the role without naming Azrael/Izra’il.

https://quran.com/en/as-sajdah/11

Tafsir Ibn Kathir on Qur’an 32:11 (English tafsir page), Ibn Kathir.

Exegetical note stating that “in some reports” the Angel of Death is called Izra’il, showing the later naming tradition inside tafsir discourse.

https://surahquran.com/tafsir-english-aya-11-sora-32.html

Is Azrael the correct name of the angel of death? (Q&A), al-islam.org editors

Explains that “Azra’il” appears in some hadith literature (as cited there) but is not named in the Qur’an, clarifying scripture vs later tradition.

https://al-islam.org/ask/is-azrael-the-correct-name-of-the-angel-of-death-and-is-there-any-source-for-it

Qur’an 2:34 (English translation)

Primary verse describing the command to prostrate to Adam and Iblis’s refusal, foundational for Islamic framing of rebellion and temptation.

https://corpus.quran.com/translation.jsp?chapter=2&verse=34

ʿIzrāʾīl (ʿAzrāʾīl), Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE (Brill Reference)

Academic reference entry defining ʿIzrāʾīl/ʿAzrāʾīl as the Angel of Death in Islamic eschatology and summarizing the tradition’s literature and development.

https://referenceworks.brill.com/display/entries/EI3O/COM-32650.xml