Japanese mythology goes beyond myths and legends; it’s a way of looking at the world. Shinto beliefs, blended with Buddhism, make up the spiritual backbone of Japan, emphasizing respect for nature and the divine spirits, or kami, that inhabit it.

Unlike in Western mythologies, where gods rule from afar, kami are everywhere, mountains, rivers, even objects have spirits. This reflects a culture deeply rooted in harmony with the natural world.

In Japan, spiritual beings range from benevolent protectors to malevolent forces, creating a balance between good and evil. Mythology tells people how to interact with these spirits.

Kitsune (foxes), for instance, may trick or help humans, while yurei (ghosts) embody grief or vengeance. Beliefs in kami mean life and spirit are intertwined, affecting everything from family rituals to national festivals.

This connection to nature and spirits isn’t abstract, it’s alive. Festivals like Setsubun, where people chant “Oni wa soto!

Fuku wa uchi!” to drive away demons, or Tanabata, celebrating wishes, show how mythology shapes daily life. The Japanese see the spiritual as a constant presence, woven into each moment.

Japanese mythology isn’t just about gods and monsters, it’s about how the living world and spirit world coexist. This respect for unseen forces underpins the myths and legends, where kami and yokai have as much influence on life as any human.

Origins of Japanese Mythology: Creation Myths and Key Deities

At the heart of Japanese mythology lies the creation story of Izanagi and Izanami. Tasked with forming the Japanese islands, they dipped a jeweled spear into the chaotic waters below.

As the drops fell, the islands of Japan were born. But creation had a price. Izanami, while giving birth to the fire kami Kagutsuchi, suffered fatal burns.

Her death marked the split between life and death. Heartbroken, Izanagi ventured into Yomi, the land of the dead, hoping to bring her back.

However, he found her transformed, “a festering corpse” whose return was impossible.

“From the spear’s dripping brine, land arose, and thus was the first island born.” – Kojiki

After escaping Yomi, Izanagi purified himself, a ritual that birthed the three most significant deities: Amaterasu, the sun goddess; Tsukuyomi, the moon god; and Susanoo, the storm god. These three, known as the Three Precious Children, are pillars of Japanese mythology.

Amaterasu represents light, warmth, and growth. Her brother Susanoo, embodying storms and chaos, contrasts her peaceful nature. Their sibling rivalry is a core myth, where Susanoo’s reckless behavior leads to a cosmic fallout.

“She gazed upon herself and light returned to all realms.” (Nihon Shoki)

In one infamous incident, Susanoo destroyed Amaterasu’s rice fields and even threw a flayed horse into her sacred hall. Disgusted, Amaterasu withdrew into a cave, plunging the world into darkness.

The other kami, desperate to restore light, devised a plan. They held a lively ritual, hanging a mirror outside the cave and performing dances until Amaterasu’s curiosity drew her out.

The world was illuminated once more as she stepped out, captured by her own reflection. “She gazed upon herself,” the Kojiki records, “and light returned to all realms.”

This myth isn’t just about sibling rivalry, it speaks to the Japanese concept of balance. Amaterasu’s light counters Susanoo’s storms, showing that harmony requires both creation and destruction.

Susanoo, later exiled, finds redemption through his encounter with the eight-headed dragon, Yamata no Orochi. He slays the beast by intoxicating it with sake, saving a maiden named Kushinada-hime.

Inside the dragon’s tail, he discovers the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, the Grass-Cutting Sword, which he presents to Amaterasu, mending their broken bond.

Through these early myths, we see themes of order versus chaos, life and death, and redemption. These deities set the stage for countless other tales, showing that Japanese mythology isn’t about one-dimensional gods but complex beings reflecting human struggles.

The myths of Izanagi, Izanami, Amaterasu, and Susanoo continue to shape Japan’s cultural identity, emphasizing cycles, respect for nature, and the power of balance.

Heroes and Warriors: Tales of Valor and Mythic Feats

Japan’s mythology isn’t all gods and spirits, it also celebrates legendary heroes. These warriors bridge the mortal and divine worlds, often battling fierce creatures or yokai to protect humanity.

One of the most famous heroes is Yamato Takeru, a prince known for his daring exploits and cunning. His story involves battling shape-shifters, beasts, and even warriors disguised as animals.

Yamato Takeru’s tale is filled with challenges. In one episode, he’s sent to conquer a tribe that uses trickery to mask their numbers.

Knowing he’s outnumbered, he uses a strategy: he lights a fire around their encampment to create chaos, seizing control. Yamato’s victories symbolize courage, wit, and resilience, qualities celebrated in Japanese culture.

His life wasn’t easy, betrayed and tested, he constantly had to prove his strength, representing the warrior’s journey against all odds.

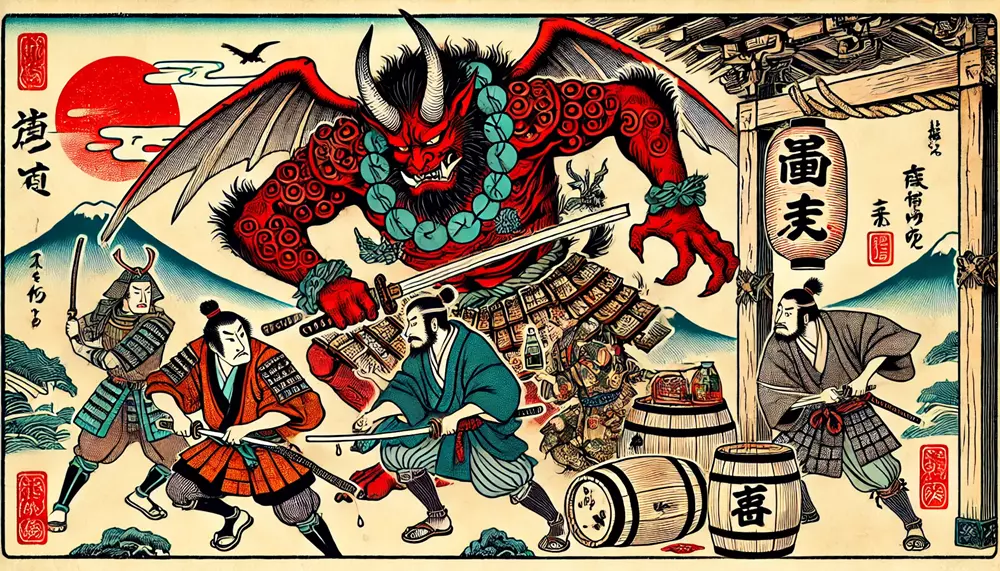

Raiko, another famous warrior, is known for his battles with oni (demons). Oni in Japanese folklore are massive, fearsome creatures with red or blue skin, horns, and a taste for chaos.

In one of Raiko’s most famous tales, he’s sent to defeat Shuten Doji, an oni lord terrorizing the region. Using guile, Raiko and his allies infiltrate the oni’s lair, offering him sake laced with poison.

Once the oni is weakened, Raiko strikes, severing Shuten Doji’s head, restoring peace to the land.

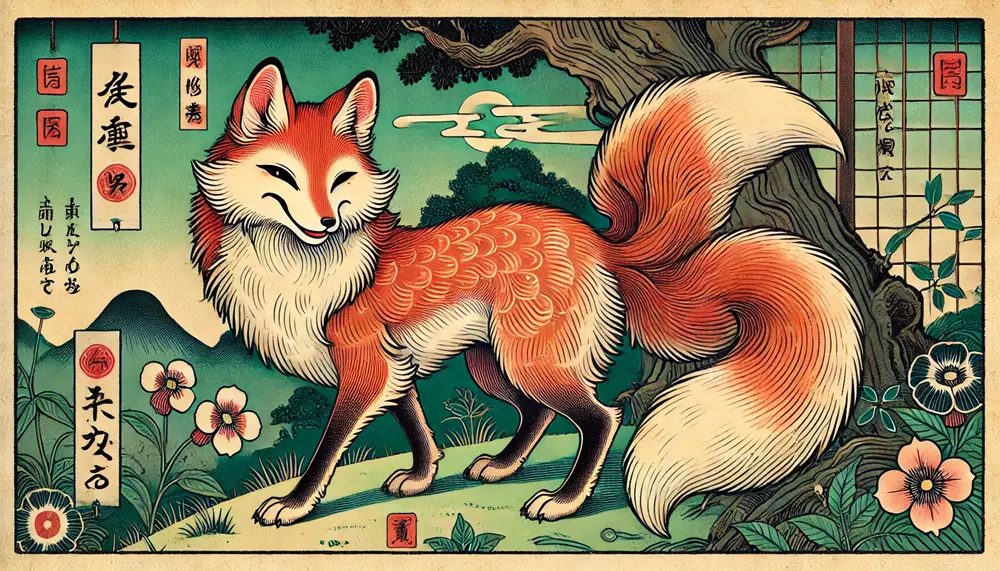

Not all creatures in Japanese myths are outright villains. The kitsune, or fox spirit, straddles the line between helpful guide and mischievous trickster.

Linked to Inari, the kami of rice and prosperity, kitsune are known for their shape-shifting abilities, often taking human form to interact with humans. In some stories, they appear as beautiful women, testing human loyalty or rewarding kindness.

Kitsune stories reflect the idea that even tricky spirits have wisdom to share, embodying nature’s duality, beneficial but unpredictable.

Japan’s heroes don’t always battle demons. Sometimes, their courage lies in confronting supernatural elements. Take Kintaro, the Golden Boy, a hero raised by a mountain witch.

With his extraordinary strength, Kintaro befriends animals and wrestles with spirits. His friendship with a bear symbolizes Japan’s respect for nature and the close bond humans can have with the wild.

Heroes like Kintaro show that Japanese mythology celebrates harmony as much as it values strength.

Legendary Beasts and Spirits of Japan

Japan’s supernatural world is rich with creatures, each carrying deep cultural symbolism. Kitsune, or fox spirits, are shapeshifters associated with Inari, the rice deity.

They’re known for playing tricks, but they can also act as protectors. In one legend, a man rescues a fox, only for the kitsune to later repay him by guiding him to fortune.

Kitsune embody both cunning and loyalty, highlighting the fine line between deception and devotion.

The yuki-onna, or Snow Woman, appears in winter storms. Often depicted as a beautiful woman with pale skin and icy breath, she can freeze her victims with a single touch.

Yuki-onna tales are haunting, capturing both winter’s beauty and danger. In one story, a young man encounters her during a storm.

She spares him, making him promise not to reveal her identity. When he later breaks this vow, she vanishes, leaving him with only the cold reminder of his broken promise.

Yuki-onna represents winter’s unforgiving side, emphasizing that nature’s beauty often comes with hidden perils.

Oni are some of the most iconic creatures in Japanese folklore. These massive, horned demons embody primal forces, rage, violence, chaos.

Stories about oni often involve fierce battles with warriors, as they raid villages and spread fear. During the Setsubun festival, families throw beans to drive away oni, symbolizing the desire to keep negativity out of the home.

“Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” (Demons out! Luck in!) is chanted, a ritual meant to maintain harmony.

Lastly, yurei, ghosts driven by unresolved emotions, are integral to Japan’s ghost lore. Unlike the playful yokai, yurei often appear in sorrowful forms, wearing white burial kimonos, with long black hair obscuring their faces.

Okiku, a famous yurei, was wronged and killed by her master, forever counting lost plates in her haunting grounds. She embodies the idea that those who die unjustly may not find peace.

Yurei tales, grounded in the belief that emotions can trap spirits, remind us of the importance of honoring the dead.

Through these mythical beings, Japanese mythology brings out the complexities of life, the unpredictability of nature, and the need to respect all beings, whether human, spirit, or beast. These tales continue to inspire, showing that even in the modern world, Japan’s supernatural legacy endures.

The Role of Kami – Spirits of Nature and Worship

In Shinto, kami are spiritual entities that inhabit everything in nature, from towering mountains to small rivers. Kami are unique; they’re not always “gods” but can be forces of nature, ancestors, or even protective spirits of places.

They aren’t distant deities; they’re right here, around us. To honor them, the Japanese set up shrines, each dedicated to specific kami who offer protection or blessings.

“Our land is one of kami, blessed and protected by the spirits.” – Kojiki

Kami influence daily life and Japanese festivals, from rice harvests to seasonal events. They’re celebrated with rituals, offerings, and festivals like the Aoi Matsuri, where people dress in traditional clothing to honor the kami of Kamo Shrine.

Even today, the Japanese turn to kami for guidance and prosperity, showing how closely connected these spirits are to daily life.

The ancient texts mention, “Our land is one of kami,” underlining how deeply this connection runs. Some kami are benevolent protectors, while others demand respect or retribution if wronged.

These spirits remind people of nature’s power and the importance of living in harmony with it.

The concept of kami reflects Japan’s view of nature and humanity as interdependent, where spirits protect or guide but can also punish those who disrupt natural balance. Kami are essential in Japanese life, reminding people of their place in a world shared with other unseen beings.

Yokai – Mischievous, Malevolent, and Mysterious Creatures

While kami are generally respected and revered, yokai take on a different role in Japanese folklore. They’re supernatural creatures ranging from tricksters to terrifying monsters, each with its own quirks and powers.

Yokai often live at the edges of society, in forests or abandoned areas, and they come in endless forms, from the playful tanuki (raccoon dogs) to the frightening jikininki (human-eating ghosts). Some yokai even help humans, but others are troublemakers who cause chaos.

One well-known yokai is the tanuki, a shapeshifter known for its mischievous pranks. Legends say tanuki can turn into inanimate objects or people, leading travelers astray for fun.

“The tanuki changes its form as the wind changes its path,” goes an old Japanese saying, emphasizing their unpredictable nature. These playful spirits represent the lighter side of yokai, providing comic relief in folklore.

“The tanuki changes its form as the wind changes its path.” – Japanese proverb

In contrast, the noppera-bo (faceless ghost) is a more chilling figure. This yokai appears human but lacks a face, and it’s often used in stories to scare children and teach caution.

The rokurokubi, a woman whose neck stretches out at night, adds to the eerie vibes of yokai tales. Her story warns against wandering at night, blending folklore with practical lessons.

Yokai play essential roles in Japanese culture, embodying the idea that spirits and strange creatures aren’t just myths, they reflect the mysterious side of nature and humanity’s desire to explain the unknown. These beings are a part of the cultural landscape, adding both humor and fear to Japan’s rich tapestry of mythology.

Sacred Stories and Symbolism in Japanese Religion

Japanese mythology is inseparable from its religious beliefs, especially Shinto and Buddhism. Shinto focuses on kami worship and rituals, while Buddhism brought concepts of the afterlife and karma.

This blend creates a unique spiritual culture where myths support religious practices and shape values. Shinto myths often revolve around purity, respect, and the cycles of life, with many shrines maintaining these practices today.

The Kojiki and Nihon Shoki are primary sources that document early Shinto beliefs. One passage reads, “The kami bestow blessings upon those who live in reverence,” emphasizing how faith and respect for nature lead to prosperity.

Shinto’s rituals are about maintaining purity and connection to nature, symbolized by torii gates, which mark sacred spaces.

Buddhism added new layers to Japanese mythology, especially ideas about death and rebirth. Yurei, the ghosts who linger, are influenced by Buddhist concepts of karmic debts and unfinished business.

Through these tales, religion in Japan becomes a guide to navigating life’s challenges, teaching respect, and offering solace in times of loss.

Religion in Japan isn’t rigid; it’s adaptable, with people often practicing both Shinto and Buddhist rituals. This flexibility allows mythology to continue evolving, making ancient beliefs relevant in the modern world.

The Haunting Allure – Why Japanese Mythology is Full of Ghosts and Spirits

Japanese mythology has an unmatched fascination with ghosts, spirits, and other supernatural entities. Yurei, or vengeful spirits, are a constant theme.

They appear in stories as unsettled souls driven by intense emotions, anger, sorrow, love, that anchor them to the living world. The Japanese concept of death is not simply an end but a journey, where the spirit’s peace depends on its relationship with the world it left behind.

This is why honoring ancestors and conducting proper rituals is so crucial in Japanese culture.

“Unresolved grievances never vanish; the spirit lingers, bound by the ties of the living.” – Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai

Yurei are often depicted in white burial clothes, with long black hair covering their faces. Okiku is a well-known yurei, a servant wronged and killed by her master.

Her spirit remains, counting plates in a haunting cycle. She embodies the phrase from Japanese folklore, “Unresolved grievances never vanish,” reminding people that actions have spiritual consequences.

Her tragic tale is about betrayal and unresolved ties, representing the cultural emphasis on justice and the fear of lingering anger.

Another ghostly figure is Taira no Masakado, a samurai who defied the imperial court and was executed. Legend has it his vengeful spirit haunted those responsible, leading to rituals to appease him.

To this day, his spirit is honored in Tokyo, reflecting the belief that powerful yurei must be respected to avoid their wrath.

Ghost stories also serve as cautionary tales. Yurei legends emphasize the dangers of dishonoring the dead or ignoring customs.

The Japanese proverb, “The living and dead tread the same path,” shows the thin line between life and death in their worldview. This belief has roots in both Shinto and Buddhism, where respect for spirits and ancestors maintains balance.

The presence of yurei highlights the idea that emotions can transcend death. In Japanese society, spirits remind people to honor relationships and responsibilities, creating a culture where myths about ghosts aren’t just scary tales, they’re reminders of what happens when bonds are neglected.

This view of spirits continues to thrive, from traditional kabuki plays to modern horror films, showing how deeply embedded these beliefs are in Japanese culture.

Mythology in Modern Japan – Tradition Meets the Contemporary

In Japan today, ancient myths blend seamlessly with modern life, a balance that’s visible everywhere. Shrines and festivals remain popular, drawing in people from all generations.

It’s not just religious tradition, these practices are a deep-rooted part of Japanese identity. Cities might be filled with neon lights, but Shinto shrines are still there, offering places for quiet reflection.

The Japanese visit shrines for everything from New Year’s blessings to exam luck, demonstrating how kami are still seen as powerful guardians.

Mythological festivals, like the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto, keep these traditions alive. This vibrant celebration honors kami through parades, music, and elaborate displays, filling the streets with energy.

These events show that myths aren’t just stories, they’re a living part of community life. Seasonal traditions like Setsubun, where people throw beans to drive away oni, are celebrated in schools and homes, preserving myths while adapting them for modern settings.

The coexistence of myth and technology is unique in Japan. People might post on social media about shrine visits or festivals, blending ancient beliefs with digital culture.

Many even see kami as guiding forces in the modern age, with rituals adjusted to fit busy lives. This fluid approach helps ancient myths feel relevant, allowing traditional beliefs to thrive in a fast-paced society.

Modern Japan’s relationship with mythology shows that these stories aren’t relics, they evolve and adapt, reflecting the needs and values of today’s world. Mythology has transformed from sacred history to a cultural backbone, uniting past and present in a way that’s truly Japanese.

Japanese Mythology in Pop Culture – From Anime to Video Games

Japanese mythology is everywhere in pop culture, from manga and anime to video games and films. These stories bring kami, yokai, and ancient heroes to life in a way that resonates globally.

In anime like Naruto, characters draw from mythological figures and themes. The kitsune, for instance, inspires Naruto’s own nine-tailed fox, Kurama, blending Japanese folklore with modern heroics.

This mix of old and new attracts audiences worldwide, introducing Japanese myths to new generations.

“The living and dead tread the same path, each respecting the other’s world.” – Japanese proverb

Films also showcase Japan’s mythical beings. Spirited Away, by Studio Ghibli, is filled with kami and yokai, like the river spirit and the witch Yubaba, capturing the beauty and mystery of Japan’s spiritual world.

Ghibli’s films often explore the boundary between humans and nature, showing how ancient beliefs about harmony with the environment continue to shape stories today.

In video games, Japanese mythology has a massive influence. Titles like Ōkami let players take on the role of the sun goddess Amaterasu, reimagined as a wolf.

The game draws heavily from myths, with each character and setting inspired by Japanese folklore. Players don’t just learn the myths, they experience them, interacting with kami and battling yokai, bringing Japanese legends to life in a modern format.

Beyond Japan, mythological creatures like yurei have inspired horror films and games. The influence of Japanese ghost stories can be seen in international horror, from The Grudge to the Silent Hill series, introducing global audiences to the chilling world of Japanese spirits.

Japanese mythology’s unique blend of beauty, horror, and mystery makes it endlessly adaptable, showing up in countless genres and formats.

This presence in pop culture has ensured that Japanese mythology isn’t just preserved but expanded, bringing ancient tales to audiences far beyond Japan. The stories of kami, yokai, and heroic spirits have crossed borders, proving that the fascination with Japan’s mythological world is as strong as ever.

Japanese Mythology’s Influence on Global Cultures

Japanese mythology hasn’t just remained within Japan; it’s influenced many other cultures, especially across Asia. For instance, the concept of kami in Shinto aligns closely with spirits in Korean and Chinese mythology, which also emphasize nature and ancestor worship.

This shared spiritual respect across these cultures shows how Japanese mythology taps into themes that resonate deeply across Asia.

The reach of Japanese mythology also extends to popular culture worldwide. Many Southeast Asian countries see Japanese anime and manga, which are packed with mythological references, as cultural phenomena.

Iconic creatures like the kitsune or the oni have become well-known outside Japan, showing up in games, films, and art far from their homeland. Japanese spirits are even portrayed in Western media, sometimes adapted to fit local folklore traditions, highlighting the universal appeal of Japan’s mystical creatures.

In Europe and North America, Japanese mythology is often romanticized, with concepts like bushido (the warrior code) inspiring everything from novels to martial arts films. Creatures like yurei have reshaped the horror genre internationally, introducing a unique blend of fear and spirituality into Western narratives.

Western and Japanese mythologies are distinct, but their interaction creates fresh storytelling opportunities, blending Eastern spirituality with Western storytelling styles.

This cross-cultural exchange has made Japanese mythology a global phenomenon. Japanese myths, which focus on harmony, nature, and mystical forces, connect with universal ideas, resonating with audiences worldwide.

The blend of Japan’s ancient beliefs with global themes has broadened the mythological landscape, bringing Japanese legends into new realms and creating a shared world of cultural icons.

Parallels Between Japanese Beasts and Global Mythological Creatures

Japanese mythology has several creatures and heroes with counterparts in other cultures, showing how universal some mythological themes are. For example, the kitsune (fox spirit) has a lot in common with the huli jing of Chinese mythology, a fox spirit that’s also a shape-shifter and trickster.

Both creatures embody the balance between wisdom and mischief, though each culture interprets them slightly differently, China’s fox spirits are often more closely tied to seduction and magic.

The oni (Japanese demons) share traits with the asuras from Hindu and Buddhist mythology. Both are powerful beings often associated with chaos and conflict.

Oni, like asuras, can be fierce enemies but are sometimes portrayed as protective guardians, showing that the line between good and evil in mythology is often blurred. This duality reflects the universal belief that strength can be used to protect or destroy.

Even heroes in Japanese mythology have parallels elsewhere. Susanoo, the storm god, can be compared to gods like Thor in Norse mythology, both known for their tempers and role as protectors.

Each has stories of challenging monsters, with Susanoo defeating the serpent Yamata-no-Orochi and Thor battling the Midgard Serpent. These heroes’ mythic battles embody humanity’s desire to face and conquer fears.

These mythological “twins” show that while Japan’s stories are unique, they share a common thread with other cultures. Themes like balance, bravery, and the supernatural resonate across the world, highlighting the shared human quest to understand life, nature, and the unknown.

Sources

Britannica – Japanese Mythology

Comprehensive resource detailing Shinto origins, major myths, and legendary figures.

Mythopedia – Japanese Mythology

Offers detailed profiles of gods, spirits (kami), and significant myths in Japanese folklore.

MythBank – Japanese Mythology Guide

Covers creation myths, major deities, and folklore stories, focusing on figures like Amaterasu and Susanoo.

New World Encyclopedia – Japanese Folklore and Mythology

Explores the origins, cultural significance, and unique myths of Japan, including the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki.

History Cooperative – Key Characteristics of Japanese Mythology

Provides insights into Japan’s core mythological themes, festivals, and prominent literary sources.