Scottish Mythology is deeply woven into its landscape, shaped by rugged highlands, mysterious lochs, and windswept islands. The tales of Scotland’s mythological beings, from ancient Pictish deities to modern folklore, offer a lens through which we can understand the nation’s cultural evolution.

This journey delves into Scotland’s mythological tapestry, beginning with ancient creatures and legends, moving through medieval tales, and exploring the modern-day interpretations and impact of these myths.

Ancient Myths and Beasts

Before written history, Scotland’s myths lived in stone, land, and voice. The Picts and early Celtic tribes believed the natural world teemed with spirits, some helpful, others deadly.

Their carvings and oral tales suggest a world where beasts served as symbols of power, transformation, and protection.

These stories predate Christianity and medieval literature, reflecting a worldview shaped by nature and mystery. Many of these creatures would later evolve in form, but their ancient roots reveal the raw, untamed heart of early Scottish belief.

Beast of Brodie – mystery on the stones

This unnamed creature appears on a Pictish symbol stone found near Brodie, Moray. With a body resembling a seal, dolphin, or horse, the carving predates written myth and likely represents a powerful water spirit.

Some believe it’s the earliest visual ancestor of the Kelpie or Each-Uisge.

Its true name is lost, but its carved image reflects how the Picts imagined supernatural forces, not as gods, but as beasts inhabiting wild rivers, guarding or destroying based on respect.

Cailleach Bheur – the hag of winter

Older than the medieval goddess archetype, the Cailleach began as a land-shaping giantess. She brings snow by striking the earth and carries stones that form mountains.

In earliest myths, she is a primal force, neither human nor divine, but elemental.

Legends say she sleeps inside mountains like Ben Nevis, awakening each winter to control the weather. Her myth may stem from ancient seasonal rites tied to survival and harvest in early Celtic Scotland.

“The holy man raised his hand and called upon the beast to halt, for its terror was not meant for men of God.” (Vita Columbae by Adomnán, c. 700 AD).

The arrival of the Celts around 1200 BCE brought new layers to Scottish mythology. Celtic deities like Cailleach Bheur, the winter goddess, personify nature’s harshness and transformation.

Cailleach is described in medieval texts as an old woman who carries stones and controls winter weather.

The Scottish poet Alexander Carmichael records her influence in the Carmina Gadelica, a collection of Gaelic folk prayers: “The Cailleach sleeps beneath Ben Nevis, but when winter awakens, so does she.” This quote captures the enduring role of Cailleach as a symbol of Scotland’s untamed natural forces.

Read more about Cailleach Bheur

Medieval Legends and Heroic Tales

The medieval period saw Scotland’s myths expand, influenced by Norse sagas, Christian texts, and Scottish bardic tradition. One of the most iconic Scottish myths is that of the selkie, a seal-like creature capable of shedding its skin to become human.

Selkie

Stories of selkies emerged primarily in the Orkney and Shetland islands, reflecting the Norse cultural impact. The selkie’s myth encapsulates themes of loss, love, and exile, resonant across Scottish folklore.

In “The Grey Selkie of Suleskerry,” a ballad from the Orkney Islands, a selkie father mourns his separation from his human family. This ballad, preserved in Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, describes the creature’s longing

“I am a man upon the land; I am a selkie in the sea. And when I’m far and far from land, my dwelling is in Sule Skerry.”

The selkie myth has endured, with each generation adding new layers of meaning that emphasize the interconnection between humans and nature.

Read more about the Selkie

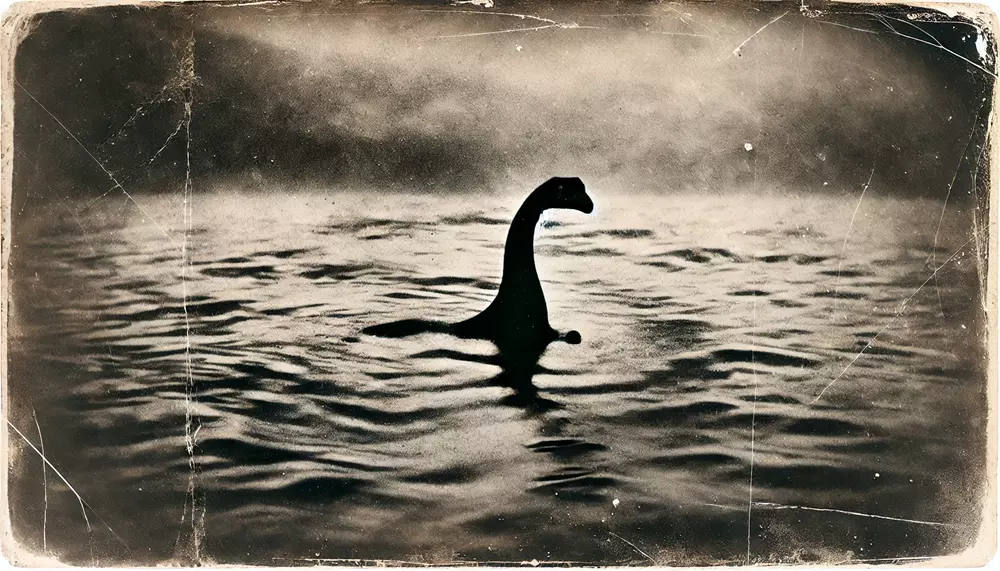

Loch Ness Monster

The Loch Ness Monster, affectionately called “Nessie,” is said to inhabit Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands. Descriptions vary from a long-necked creature resembling a plesiosaur to shadowy humps moving across the loch.

The earliest recorded mention comes from Adomnán’s Vita Columbae (7th century), where St. Columba repelled a water beast with prayer.

Over centuries, Nessie grew into a symbol of mystery, drawing countless sightings, hoaxes, and expeditions. Today, she embodies Scotland’s enduring connection to legend and its power to inspire awe.

Read More about the Loch Ness Monster

Bean Nighe – washer of the ford

The Bean Nighe is a ghostly figure from Scottish folklore who washes bloodied clothes at river fords, foretelling death. If you see her cleaning a shirt with your name on it, it means your time is near.

She is often described as small, haggard, and weeping.

Despite her eerie presence, she’s not evil. In some versions, if caught and questioned, she’ll reveal who is going to die, or even prevent it.

She’s considered a Scottish cousin to the Irish Banshee.

Read more about Bean Nighe

Cù-Sìth – green hound of the sidhe

The Cù-Sìth is a massive fairy hound with green fur and glowing eyes, said to roam the misty moors of Scotland. As a creature of the sidhe, it serves as both guardian and harbinger of doom, barking three times before a death occurs.

Its eerie howls can be heard miles away, and those who hear them must reach safety before the final bark. Though tied to ancient beliefs, tales of the Cù-Sìth still echo in modern Scottish folklore.

Read more about Cù-Sìth

Each-Uisge – The Devouring Water Horse

The Each-Uisge (“ech oosh-ka”), meaning “water horse” in Gaelic, is among the most dangerous water spirits in Scottish folklore. Unlike the kelpie, which inhabits rivers, the Each-Uisge lurks in lochs and the sea.

It can appear as a handsome horse, a man, or a bird.

Legends warn that if anyone mounts the Each-Uisge, they cannot dismount. The creature’s skin becomes adhesive, trapping the rider.

It then dives into the deepest water, devouring its victim entirely except for the liver, which floats to the surface.

Descriptions emphasize its uncanny beauty and power. When in human form, it may betray itself with telltale features like waterweed in its hair.

Highland communities passed down these stories as stark warnings about the peril of lochs, especially for children.

The Each-Uisge represents both the allure and the danger of untamed waters. Unlike the kelpie, which is sometimes tamed in folklore, the Each-Uisge is always lethal.

Its legend underscores the constant fear of drowning in Scotland’s wild highland lochs.

Shellycoat – The Mischievous Trickster

The Shellycoat is a lesser-known but distinctive figure in Lowland Scottish folklore. This water spirit takes its name from the rattling coat of shells it wears, clattering as it moves along the riverbanks.

Unlike malevolent beings such as the kelpie or Each-Uisge, the Shellycoat is mischievous rather than murderous. Tales describe it delighting in misleading travelers with false cries for help or luring people into bogs and streams.

Its shell-covered attire gives it a comic, almost clownish aspect. The sound of rattling shells often announced its presence, making it hard to approach unseen.

Because of this, people feared encountering it on lonely paths or river crossings at night.

Folklorists interpret the Shellycoat as a trickster spirit tied to dangerous landscapes like marshes and riverbanks. Rather than embodying outright evil, it symbolized the hazards of misjudgment, distraction, and the wild unpredictability of nature.

Blue Men of the Minch

The Blue Men of the Minch, also called storm kelpies, are supernatural beings said to inhabit the waters of Scotland’s Minch strait. Described as blue-skinned men with flowing green beards, they dwell beneath the sea but rise during storms.

Legends say they challenge sailors with riddles. If the captain cannot answer, the Blue Men summon gales to capsize the ship.

When they chant, disaster is near; when they fall silent, calm may return.

Their lore connects them to ancient sea gods, perhaps echoing Norse influences. Sailors feared them as omens of drowning and destruction.

Yet, in rare stories, they spared ships if bested in wit, showing a dual nature of both menace and challenge. They embody the dangers of the Minch’s stormy waters and the thin line between life and death at sea.

The Influence of Christianity and Syncretism on the Scottish Mythology

With the spread of Christianity in the early medieval period, many traditional Scottish mythologies were either transformed or subsumed within Christian teachings. St. Columba, a Christian missionary in the 6th century, reportedly encountered a “water beast” in Loch Ness, now famously associated with the Loch Ness Monster.

According to the Vita Columbae, written by Adomnán, St. Columba repelled the creature with a prayer, symbolizing Christianity’s conquest over pagan beliefs.

This account is one of the earliest recorded mentions of a mythological water creature in Scotland, linking ancient lore with Christian symbolism.

During this period, figures like the Cailleach were reinterpreted within a Christian framework, becoming moral symbols rather than deities. As Scottish folklore adapted to the new religious landscape, Cailleach Bheur’s winter powers came to represent not just natural cycles but also the moral lessons of endurance and resilience.

Seonaidh

Seonaidh (pronounced “shonny”) is a water spirit from Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Seonaidh was invoked in ritual rather than feared as an enemy.

Islanders offered ale to him, pouring it into the sea at night as sacrifice. These rites were believed to secure a good fishing season.

Seonaidh was envisioned as a powerful underwater being, not necessarily malevolent, but one who demanded respect and appeasement. His presence reflects the deep ties between island communities and the sea that sustained them.

Seonaidh embodies both bounty and danger, a reminder that survival depended on maintaining harmony with the unseen forces of the ocean. His lore is less about terror and more about balance, a contract between people and the wild sea.

Renaissance and Enlightenment: Rationalization of Myth

The Renaissance and Enlightenment brought an era of questioning and skepticism to Scottish Mythology.

Mythical creatures were increasingly viewed through a rational lens. Many scholars and historians sought to explain away supernatural accounts with natural or psychological explanations.

For instance, the kelpie, widely feared as a predatory water spirit, began to be seen as a cautionary tale to prevent children from venturing too close to dangerous water bodies.

Scottish poet James Macpherson famously brought the legendary figure Ossian into the literary world in the 18th century, purportedly translating ancient Gaelic poems. His works were widely celebrated, though later critics questioned their authenticity.

Nonetheless, Ossian became a symbol of Scotland’s mythic past, celebrated by figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and influencing European Romanticism.

Nuckelavee – skinless terror of the Orkney Isles

The Nuckelavee is a grotesque sea-demon from Orkney folklore, often described as horse-like with a human torso fused to its back. It has no skin, just raw, exposed muscle, and its breath withers crops and spreads plague wherever it roams.

The creature is feared above all others in the northern isles. Only fresh water can stop it, as it cannot cross running streams.

The Nuckelavee is a rare example of a purely malevolent being in Scottish myth.

Read more about Nuckelavee

Baobhan Sith – the vampiric fairy of the Highlands

The Baobhan Sith is a deadly fairy from Highland lore, often taking the form of a beautiful woman in a green dress. She appears at night to lone travelers or hunting parties, inviting them to dance, then drains their blood while they sleep or rest.

Despite her elegance, she is a predator. Legends say she avoids iron and sunlight. The Baobhan Sith blends the charm of the fae with the danger of a vampire, haunting Scotland’s remote glens.

Read more about Baobhan Sith

Ghillie Dhu – the gentle forest guardian

The Ghillie Dhu is a solitary fae spirit from Scottish folklore, known for dwelling in birch groves near Gairloch. Described as small and dark-haired, he wears living foliage as clothing and blends perfectly with the forest.

Unlike other fae, he is kind-hearted and especially protective of lost children.

First stories surfaced in the 17th century, portraying him as shy but harmless. While rarely seen, he represents the gentler side of the Scottish fae – an elusive figure tied to nature’s quiet magic and woodland mystery.

Read more about Ghillie Dhu

The Modern Era: Enduring Legends and Pop Culture Revivals

Today, Scottish myths have become an integral part of global pop culture, yet they retain their regional essence. The Loch Ness Monster, affectionately called “Nessie,” stands as a modern symbol of mystery and tourism, with countless reported sightings and scientific expeditions attempting to validate or debunk the myth.

Modern interpretations of Nessie vary widely, from the possibility of a plesiosaur surviving in the loch to an embodiment of Scotland’s enduring mystery.

The Wulver’s True Nature

Unlike most beasts in Scottish folklore, the Wulver is defined by empathy rather than terror. With the body of a man and the head of a wolf, he lives alone, avoids conflict, and quietly aids struggling families by leaving fish at their windows.

Jessie Saxby’s 1932 account remains the only authentic source, describing the Wulver as a solitary figure connected to a stone he fished from. Though many have tried to link him to werewolves or Norse spirits, the Wulver stands apart, a creature not born of curse or vengeance, but of quiet generosity and enduring mystery.

Read more about the Wulver

Kelpie – the shape-shifting water horse

The Kelpie is a supernatural water horse said to haunt Scotland’s lochs and rivers. Usually appearing as a beautiful black horse, it lures people onto its back, only to drag them underwater.

Its skin becomes sticky, trapping riders before it vanishes into the depths.

Some tales describe it taking human form, often with wet hair and water-weed clinging to its body. The Kelpie legend served as a warning, especially to children, to stay away from dangerous waters.

Read more about the Kelpie

Cultural Impact and Symbolism in Scottish Mythology

Scottish Mythology has had a lasting influence on cultural traditions, symbols, and national identity. The unicorn, Scotland’s national animal, is rooted in Celtic symbolism, representing purity and strength.

This creature appears in medieval Scottish coats of arms, often portrayed in chains, reflecting a complex symbolism of untamed beauty constrained by state authority.

Celebrations such as the Beltane Fire Festival in Edinburgh draw from ancient Celtic rituals, celebrating the cycle of life and death symbolized by Cailleach Bheur’s transition from winter to spring.

In this festival, performers often embody mythological beings, such as the Green Man and the May Queen, bridging the ancient past with modern celebration. Beltane is a testament to Scotland’s commitment to keeping its mythological heritage alive.

The enduring symbolism of these creatures has also influenced Scotland’s literary and artistic traditions. Authors like Robert Louis Stevenson and Neil Gaiman have woven Scottish folklore into their works, ensuring that these ancient tales continue to captivate new audiences.

As Stevenson wrote in Kidnapped, “It is upon the faith of tales like these that nations grow old and keep their wisdom.” This line encapsulates the importance of myth in preserving cultural wisdom and continuity.

Scientific and Rational Explanations

While myths persist, scientific explanations have challenged their literal interpretations. For instance, the kelpie has been explained as a misinterpretation of the behavior of natural wildlife, such as otters or seals.

Similarly, the Loch Ness Monster sightings have been attributed to floating logs, wave patterns, or even hoaxes. Historian Richard Frere, in his analysis of Nessie sightings, argues that the myth persists due to its emotional appeal, which transcends scientific explanation: “Nessie is not just a creature; she is a guardian of the unknown” (Frere, Loch Ness: A Century of Sightings).

Conclusion

From ancient Pictish carvings to modern-day festivals and media portrayals, Scottish mythology represents a continuum of cultural expression, blending folklore, history, and imagination.

Each era has added its interpretation, shaping myths to reflect contemporary values and challenges. Whether through the legends of selkies, the reverence for Cailleach Bheur, or the mystery surrounding Nessie, Scotland’s mythological heritage serves as a mirror to its natural landscape and national spirit.

These legends, continually retold, reveal Scotland’s resilience and adaptability, testifying to the nation’s deep-rooted sense of identity and connection to its mythological past.

Bibliography/References

Scottish Maritime Museum – Here be Monsters! Sea Monsters of Scottish Folktale

An exploration of sea monsters in Scottish folklore, including tales of creatures like the Fastitocalon.

https://www.scottishmaritimemuseum.org/here-be-monsters-sea-monsters-of-scottish-folktale-by-shelby-judge/

Scotland.org – Scottish myths, folklore and legends

An overview of various Scottish myths and legends, including the origins of selkies.

https://www.scotland.org/inspiration/scottish-myths-folklore-and-legends

Wilderness Scotland – Scottish Water Mythology: Selkies and Kelpies

Discusses the roles of selkies and kelpies in Scottish water mythology.

https://www.wildernessscotland.com/blog/scottish-water-mythology-selkies-kelpies/

The History Press – Folk tales from the Scottish coastline

A collection of folk tales from Scotland’s coastline, highlighting various mythical creatures.

https://thehistorypress.co.uk/article/folk-tales-from-the-scottish-coastline/

VisitScotland – Discover Scottish Myths & Legends

Provides insights into Scottish myths and legends, including creatures like Morag and Nessie.

FAQ

Baobhan Sith compared to Loch Ness Monster and Selkie

| Aspect | Baobhan Sith | Loch Ness Monster | Selkie |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Origin traces back to ancient Celtic beliefs and folklore. | Originated from Scottish folklore, symbolizing mystery and fear. | Originated from Celtic tales, embodying transformation and love. |

| Habitat | Typically associated with the highlands and remote areas of Scotland. | Primarily linked to Loch Ness, a deep freshwater lake. | Found along the coasts of Scotland, especially in the Hebrides. |

| Appearance | Often depicted as a beautiful woman with vampiric traits. | Described as a large, serpentine creature with a long neck. | Usually portrayed as a seal that can transform into a human. |

| Abilities | Known for luring victims to their doom with charm. | Fabled to possess the ability to disappear and reappear. | Can transform between seal and human forms, showcasing duality. |

| Cultural Significance | Represents the darker aspects of Scottish folklore and nature. | Symbolizes the mystery and allure of Scotland's natural beauty. | Embodies themes of love, loss, and the connection to the sea. |

| Modern Interpretations | Modern tales often depict it as a cryptid, sparking curiosity. | Continues to inspire tourism and media, enhancing its legend. | Contemporary stories focus on themes of identity and belonging. |